Keywords: Circular Cities, Sustainable Urban Development, Behavioural Change, Small Town Innovation

1. Introduction

Circular economy cities are emerging as a key model. Today, India is at a decisive moment in its urban development. Cities are not just the engines of economic growth, innovation and cultural transition, but also centres of climate resilience, resource management and social inclusion. According to the World Bank report, the urban population of India was about 480 million in 2020, which would almost double to 951 million by 2050. Due to this rapid urbanisation, India would be at the forefront of the world (worldbank.org). This expansion will enhance improved service priority, economic opportunities and connectivity potential; however, it will also intensify serious challenges such as degradation of air quality, reduction in groundwater stock, and degradation of ecosystems due to unplanned urban expansion. The pressure on land, energy and infrastructure in metros like Delhi and Mumbai is pushing urban life to volatility.

Moreover, the effects of urbanisation are not limited to metropolitan cities. Small and medium-sized cities are also rapidly transforming. However, given their limited resource potential, institutional capacity, and financial possibilities, without sustainable planning, these cities are also in danger of repeating the mistakes of metropolitan cities. This underlines the need for a systematic and long-term approach at all levels.

In this context, the concept of circular cities is becoming of special importance internationally. As opposed to the conventional ‘tech-make-disposal’ model, the circular approach is based on closed-loop systems where emphasis is laid on recycling, reuse and reproduction of resources. According to the UNECE guideline, such urban systems need to evolve within the framework of material flow analysis, recycling management, local participation, and strategic coordination (unece.org). In the Indian context, the promise of this approach is particularly impressive. The outlook is particularly optimistic for India, with the IBEF reporting that its waste management indicators were better on the poverty line by 2021 than the 2014 baseline, and with the potential for the circular economy to generate US$624 billion in revenue by 2050 (ibef.org).

In line with this, it is important to highlight that today, globally, we have diverse approaches such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), Circular Economy (CE), as well as ESG (Environmental, Social, Governance) frameworks. With the help of these tools, developing countries can outline national, regional and urban development and can achieve more sustainable development than developed countries by taking appropriate policy decisions. But unfortunately, most of the developing nations are still running behind rapid and Unilateral development. In such a scenario, adoption of circular economy at the right time and with rigour can set the tone for all-round sustainable development.

However, sustainable transition cannot be achieved by relying solely on policy frameworks and technological interventions. The day-to-day behaviour of urban citizens – consumption patterns, transport choices, waste management, and resource use – is a determinant of change. Research shows that without large-scale behaviour change, approaches to circular urban systems can only be limited to conceptual or policy documents (UN-Habitat, 2020; OECD, 2022). Therefore, the vision of circular cities is difficult to materialise without the active involvement of socio-cultural factors and citizen participation. This article, therefore, explores India’s urban future through three interconnected dimensions:

- The scale and nature of its rapid urbanisation,

- The emergence and potential of circular cities, and

- Emphasising on why behavioural changes are necessary in citizens to realise the specific challenges faced by both metropolitan centres and small cities.

Weaving these threads together, the discussion highlights not only the urgency to rethink India’s urban pathways but also the opportunities to shape cities that are more livable, inclusive, and environmentally responsible.

1.1 Dual Dimensions of urban transition of India

India’s urbanisation journey is not just rapid, but a structural socio-economic transition. It is estimated that about 30 persons per minute migrate to urban areas in search of employment, education and a higher standard of living. While the urban population was 31 per cent in 2011, it is projected to reach more than 43 per cent by 2035, reaching up to 675 million (The Economic Times, 2022). The extent of the transition is evident from the fact that it was only 17 per cent at the time of independence.

Urbanisation has contributed more than two-thirds of India’s GDP, according to World Bank and PwC reports (World Bank, 2025). However, with this growth, cities are becoming symbols of inequality, environmental stress and inadequate infrastructure. Traffic jams, air pollution, frequent flooding caused by precipitation, and the disorganization of public services have become features of urban life. Unplanned expansion is degradation of agricultural land and ecosystems and exacerbating water scarcity and urban heat island effect (TIME, 2024).

Therefore, urbanization in India is a multi-faceted socio-economic and environmental challenge and not just a demographic trend. Against this backdrop, the primary goal of urban policies should be to achieve a balance between development, human well-being, and ecosystem stability.

1.2 Circular Cities: A New Paradigm Towards Sustainability

In response to the pressures created by urban expansion, the concept of circular cities is emerging as an alternative and long-term guiding framework. Traditional cities operate on a linear model of ‘take-make-dispose’, where resources are discarded after use. On the contrary, circular cities are based on closed-loop systems, where resources are recycled, recovered, and regenerated – that is, waste is reduced, and the value of resources is retained for as long as possible (UNECE, 2021).

This is not just a conceptual framework; some cities have already set examples at a global level. For example:

- Amsterdam (Netherlands): Circularity has been mainstreamed in the construction sector with the introduction of the ‘Material Passport’ system

- Singapore: The NEWater project is a leading example of a city-wide initiative to recycle and treat wastewater for drinking and industrial purposes; as well as its Waste-to-Energy initiative is also leading the way.

- Copenhagen (Denmark): A target has been set to become carbon-neutral by 2025, which is sought to be achieved through waste management and the use of renewable energy.

Such a concept is also being practically implemented in the Indian context as well.

- Indore (Madhya Pradesh): Indore has consistently ranked first in cleanliness due to citizen-based waste segregation, door-to-door collection, and biogas plants (MoHUA, 2021).

- Pune (Maharashtra): Formal inclusion of waste collectors by SWaCH Cooperative, as well as decentralized composting initiatives are examples of spatialised waste valorisation (Chikarmane, 2012).

- Nagpur (Maharashtra): Sewage-to-energy projects has led to the incorporation of circular principles in both water and power sectors.

The above examples clearly depict that circular cities are not only an environmental necessity but also act as a powerful tool for social inclusion and economic sustainability. For India, adopting circular principles can be transformative. Cities consume an estimated 78 percent of global energy and generate a significant amount of waste, so a circular approach provides a way to separate growth from environmental degradation.

1.3 The spectrum of challenges in small towns and metropolitan areas

India’s urban landscape is diverse with varied but distinct challenges. In metropolitan cities like Delhi, Mumbai, and Bengaluru, population explosion, infrastructure stress, severe air and water pollution, and exhausting traffic jams are a constant reality. The growth of informal settlements in these cities, characterized by their lack of civic amenities, environmental degradation and overcrowding, have made life difficult for the residents. In such a situation, low-carbon infrastructure, efficient waste management, and the adoption of renewable energy are urgently required as policy measures—but their implementation has been slow due to various political and administrative hurdles (Financial Times).

Smaller to medium-sized cities, on the other hand, have a similar but more volatile capacity for extremes. Financially and institutionally, inadequate capacity, lack of technical training, limitations in tax collection, and low availability of funds in such a city ultimately affect the quality of infrastructure, housing, sanitation, sewage, and waste management (CSR EducationThe WireDrishti IAST The Times of India).

In particular, untreated sewage, dumped garbage and unplanned settlements—all of which can be found in smaller towns—can be the source of significant amounts of untreated biological pollutants. Such cities can also lead to significant ecological, social, and economic imbalances and stresses, which can have lasting effects on their development. Therefore, the factors that will shape India’s urban character are not just the metropolis, but also how effectively small and medium towns are managed.

1.4 Behavioural Adjustment: An Imperative Foundation of Urbanisation

The development of sustainable cities is based on the transformation of the daily behaviour of its citizens, not just policy and technological achievements. Various studies demonstrate that individual actions can result in significant societal change, such as through actions like recycling, water conservation, reducing dependence on private vehicles, and selecting energy-efficient appliances (Springmann et al., 2016; World Bank, 2025). However, simply providing information is not enough to change behavior; nudges, when implemented according to positive-conditioning and social and moral factors, make environmental decisions easier, more attractive, and socially acceptable (Rare, 2020; WWF, 2024).

At the institutional level, the use of persuasive media – such as circulars in schools, campaigns targeted at families and communities, as well as promotional policies – seems to shape sustainable behavior. For example, NGC (National Green Corps) eco-clubs in Indian schools and the participation of student-movements under the ‘MY Bharat’ campaigns (such as plastic-free public places, tree plantation, zero-emission day activities) are helping students become active environmental citizens (NGC; Delhi Education Initiative, 2025).

It is necessary to understand that behavioral changes are not simply manipulation of habits, but a process of changing reality in the mindset. Cities are “co-created spaces” and citizens need to share this responsibility, for which the following technological solutions can be effective:

- Literacy and Education: By incorporating circular principles not only in subjects but also through stories, science skills, and practical experiments (e.g., environmental workshops, robotics-based activities, climate-awareness initiatives) can build sensitivity among students for a sustainable world (Horasis, 2023; Earth.org, 2024; Arxiv, 2022).

- Structural availability of urban alternatives (Choice Architecture): Making environmental decisions in cities easier, more attractive, and socially ideal—for example, local initiatives such as shared rainwater harvesting, community composting, and cafe remodelling – motivates members.

- Incentive-based policies: Policies such as property tax rebates for houses that segregate waste, ‘Green Campus’ certification, and grants for eco-friendly houses can change community behaviour in a positive direction (EAC-PM, 2023).

Ultimately, circular cities are not just shaped by infrastructure and technology – they are a culture that is embraced by ordinary people in their daily lives. The sustainable transition in the city will be incomplete without behavioural change among citizens.

Article 1 – Circular Cities in India: Problems and Opportunities (Mr. Sameer Summers)

Why did I choose this article?

I chose Mr. Unhale’s article because it raises a timely issue of applying the principles of the circular economy to Indian cities. His article connects urban challenges – waste, water, and energy – with practical opportunities for circular solutions.

Rationale

This article aligns with my purpose of examining how circularity can be practically applied within a policy framework. Concrete examples of this, such as compost certification, wastewater treatment, and renewable energy, serve as valuable entry points for sustainable urban policies.

Response Review

Mr. Unhale criticizes the “linear” growth model and strongly advocates for circular systems. His case studies – Maharashtra’s Green Compost Program, the city’s waste-to-energy project, and the sewage-to-resource models – illustrate how circularity can generate environmental and economic benefits. The inclusion of renewable energy projects strengthens the link with India’s climate commitment.

However, there are still significant barriers: scale-up of pilot projects, limited municipal capacity, weak financing, and lack of citizen participation. This article could have focused more on the institutional integration of informal waste sectors and data-driven technology capabilities, as these elements are essential for accelerating circular city transitions.

Conclusion

Mr. Unhale’s article highlights the urgency of circularising Indian cities. While the policy framework provides guidance in the right direction, its actual impact depends crucially on local institutional capacity, inclusive urban governance, and the active participation of citizens.

Article 2 – Small Cities and Urbanization (By Mr. Amit Dubey)

Why did I choose this article?

I selected Mr. Dubey’s article because it highlighted the role of small and medium towns, which are often overlooked in urban debates but are crucial to India’s sustainable future.

Rationale

This approach complements the discussion of circular cities with an emphasis on spatial dimensions. Smaller cities face rapid but resource-intensive growth, making them vulnerable and uniquely positioned to adopt circular practices early on.

Response Review

Mr. Dubey identifies key obstacles in small towns: limited infrastructure, economic weakness, and fragile governance. However, he also points to opportunities for local circular practices like decentralized waste management, composting, and water reuse. Small towns can innovate faster than large cities burdened by bureaucracy.

I agree with his perspective, but I extend it further: limiting circularity to metropolitan regions risks creating a two-tier urban India. For equality and long-term resilience, it is essential to mainstream circular practices in smaller cities. By considering smaller cities as circular innovation labs, India can create models that can be emulated by larger cities.

Conclusion

Dubey’s article shows that India’s sustainability cannot solely depend on metropolitan solutions alone. It is crucial to expand the circular approach in smaller cities to avoid repeating the mistakes of megacities and promote balanced, equitable urban development nationwide.

Article 3 – Behavioural change for sustainable cities (Mr. Dhiraj Santdasani)

Why did I choose this article?

I chose Mr. Santdasani’s article because it highlights the human dimension of sustainability — the attitudes and behaviours of citizens that are often overlooked in policy and planning.

Rationale

Circularity is not limited to policies and technology; it depends on how citizens view consumption, waste, and shared responsibility. This article aligns with my interest in incorporating community participation into urban sustainability.

Response Review

Mr. Santdasani strongly argues that a circular economy is at risk of becoming a technical exercise without citizen participation. Practices like waste segregation, water conservation, and repair and reuse are crucial at the household level. At the community level, initiatives like neighbourhood composting and cafe repairs promote inclusivity and ownership.

I firmly agree. Circulars should be lived every day, not just legislated. However, systematic efforts are needed to achieve this: government-led awareness campaigns, curriculum reforms to incorporate sustainability into education, and incentives to make sustainable choices attractive and achievable (For example, tax exemptions, utility discounts).

Conclusion

Santdasani’s article reminds us that behavioural change is the cornerstone of sustainable cities. Without changing citizens’ habits and mindsets, the circular will remain merely a policy statement. Transforming sustainability into practical action requires incorporating awareness, encouragement, and shared responsibility.

My integrated approach:

Circular cities in India have immense potential, but a holistic approach balancing strategic orientation, local realities, and citizen participation is needed to realize this vision. Mr. Unhale’s article aptly highlights the principles of the circular economy in an urban context, illustrating practical examples such as waste-to-energy, compost certification, and water reuse projects. His emphasis on the adoption of renewable energy, particularly biogas and solar power, reflects how circularity can be adapted to India’s climate goals.

At the same time, scaling up such initiatives beyond pilot projects remains a critical challenge, especially in smaller cities where institutional capacity and financial resources are limited. Without a comprehensive framework and citizen participation, the document risks becoming a tool for elite-driven urban projects rather than a catalyst for transformative change in diverse urban realities.

This is where Mr. Dubey’s perspective on small towns becomes significant. While urban policy often focuses on metropolitan regions, India’s next wave of urbanization will occur in small and medium towns. Instead of being peripheral, these cities can become laboratories of circular innovation through local waste management, community-driven composting, and decentralized water reuse. By incorporating circular approaches early on, small cities can avoid repeating the unsustainable growth patterns of megacities and instead set the model for large urban centers to follow. It is also a matter of equity to ensure circularity here, which prevents the emergence of a two-way urban India divided into sustainable metropolises and backward small towns.

However, policies and infrastructure alone cannot drive this transformation. As Mr. Santdasani highlighted, the success of circular cities ultimately depends on human behavior. Circularity is not just technical or administrative; it is cultural. Daily citizen practices of waste segregation, water conservation, responsible energy use, and a preference for recycling are fundamental to determining the circularity of the loop. Beyond the environmental benefits, citizen-led initiatives such as community composting or repair networks create inclusivity, social bonds, and a sense of ownership in the neighbourhood. However, achieving this change requires systematic investment in awareness campaigns, education, and incentives that facilitate and benefit sustainable choices.

Thus, India’s path towards circular cities must include national and state-level policy directions, grassroots engagement, inclusive governance, and realistic local assessments. Small towns should be empowered as centers of innovation, while behavioral changes should be nurtured to bring sustainability to daily urban life. Only by integrating policy, equity, and citizen participation can the vision of a circular city be developed from aspiration to living reality in India’s diverse urban landscape.

Comparative Analysis:

A close reading of the three articles reveals both shared concerns and specific perspectives on how India can steer its urban future towards sustainability.

Common threads:

All three authors agree that the traditional linear model of urbanization, marked by unplanned growth, excessive resource extraction, and increasing waste, is unsustainable.

Everyone emphasizes the urgency of turning to circularity, where resources are recycled and regenerated instead of being discarded. Sustainability cannot be achieved solely through infrastructure and policy measures; it requires a comprehensive systemic change involving administration, institutions, and communities, which is another integrated concept.

Different Perspectives:

Despite this common foundation, each article approaches the issue from a distinct perspective. Sameer Unhale highlights the policy and foundational dimensions of the circular, giving concrete examples of waste-to-energy projects, water reuse, and the integration of renewable energy. The article on small cities emphasizes the spatial dimension and argues that small urban centers, often overlooked, should become central laboratories for circular innovations. The third article, focusing on behavioural change, emphasises the human dimension and reminds us of that risk reduction in disaster response must be based on a technical agenda, without neglecting the needs of citizens in their daily lives.

Correlation between circularity, small towns, and behavioural change:

When viewed together, these perspectives are not separate but are deeply interconnected. Circularity provides a broad framework defining the principles of resource efficiency and reproduction. Smaller cities represent important areas where these principles can be tested, adapted, and scaled in ways that are more flexible than large metropolises.

Meanwhile, behavioral change is the glue that holds social cohesion together, ensuring that both policies and local experiments are successful on the ground. Without citizen participation, the circularities in small towns or cities will remain incomplete; without viable policies and models, behavioral change alone cannot sustain transformation.

New pathways for a sustainable urban future:

Bringing these three dimensions together opens new avenues for India’s urban future. A sustainable model emerges when policies enable circularity, smaller cities act as incubators for innovation, and citizens drive change through conscious behavior. This trinity can create cities that are not only resource-efficient but also socially inclusive and resilient to climate challenges. Such an integrated approach ensures that sustainability is not just limited to urban landscapes but is extends to the entire urban sector, thus ensuring a regenerative, equitable and future-ready form of development for India.

Recommendations:

Based on the three-pronged approach, several actionable recommendations have been derived to shape India’s urban future.

A. For policymakers (central, state, and municipal governments)

1. Prioritize circular city strategies in small and medium-sized cities

- State governments should establish dedicated funding sources to support circular initiatives in smaller cities, including decentralized waste management, adoption of renewable energy, and subsidies for water recycling projects.

- The Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs should mandate a city-level circular assessments as part of urban planning, linking them to the parameters of the Smart Cities Mission.

2. Creating an enabling legal and institutional framework

- Local bodies should mandate housing societies, hotels, and restaurants to manage and process wet waste in their own premises through appropriate decentralized systems such as composting or bio-methanation. Municipal collection services should be limited to dry waste from these societies. And to ensure compliance, appropriate penalties should be imposed on non-implementing societies.

- The State Government should frame bye-laws, rules and regulations in this regard.

- States should also start training and capacity building programs for municipal staff, cleaners and local entrepreneurs to take up recycling initiatives.

3. Strengthen measures for social equality

- To integrate informal waste workers into formal systems by providing training, legal recognition, protective equipment, and access to health care.

- Promoting gender sensitive circular economy initiatives by supporting women self – help groups in recycling, composting and resource recovery industries.

B. For urban planners and local government

4. Strengthening citizen participation in urban planning

- Urban Local Bodies (ULBs) are to set up Ward Level Steering Committees and Neighborhood Level Forums to involve citizens in local planning.

- City governments should use participatory tools such as citizen audits and green budgeting to ensure accountability.

5. Promoting education, awareness and behavioural changes

- The Ministry of Education should integrate circular and sustainability into the school curriculum and vocational training programs.

- State Governments should also take up awareness campaigns, particularly on Swachh Bharat Abhiyan themes of reducing, repairing and conserving resources.

- Offer incentives such as discounts on property/utility bills for those households and housing societies that effectively practice waste segregation and recycling.

C. For citizens and civil society

6. Promoting collaborative partnerships

- NGOs and civil society organisations should be engaged to provide training, capacity building and support for circular practices at the grassroots level.

- Private industry should be encouraged to innovate in circular business models such as reverse logistics, extended producer responsibility (EPR), and shared mobility platforms.

- Citizens should be empowered to take up community-level initiatives such as composting centres, repair cafes, and rainwater harvesting.

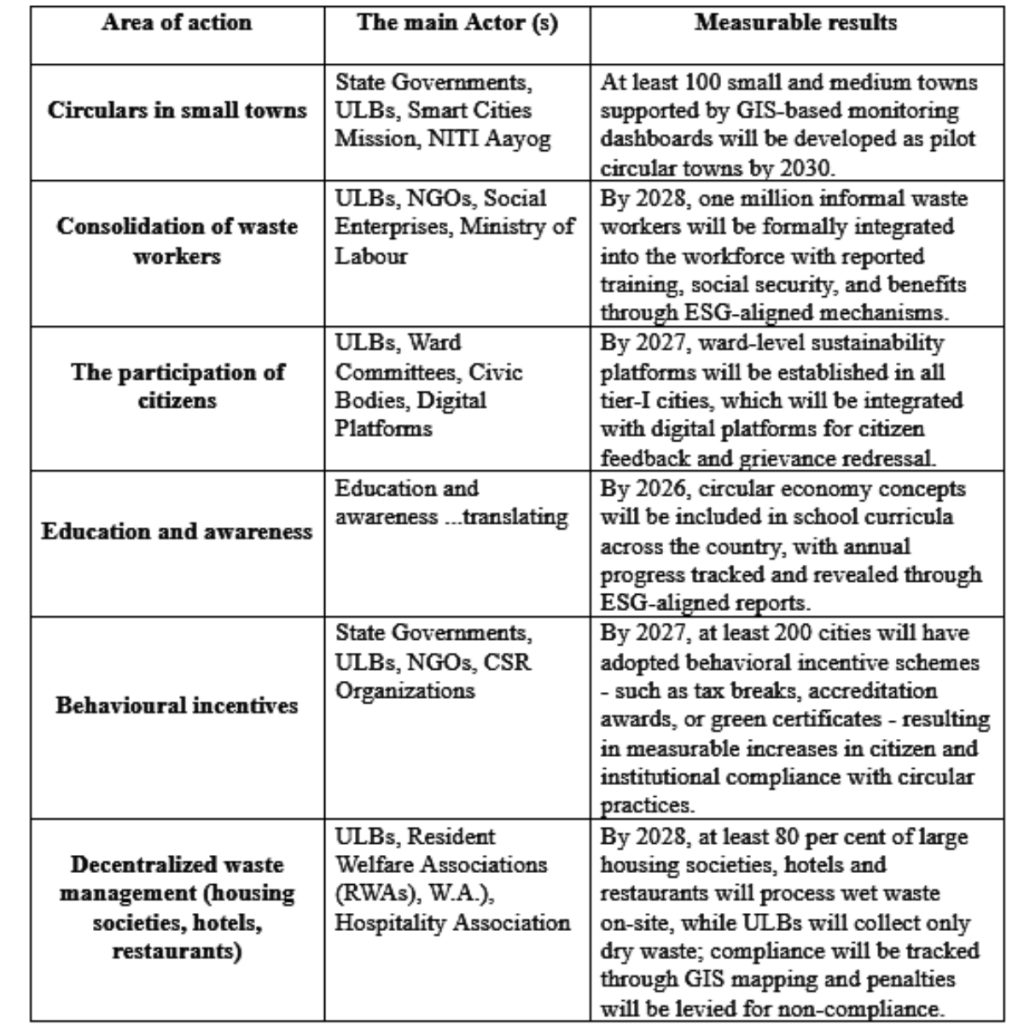

Summary Table: Key Policy Actions

The table below outlines the strategic actions recommended for advancing the City Planning Policy in India. Each action area specifies the responsible key components and measurable outcomes to be achieved within a defined timeframe, ensuring clarity, accountability, and alignment with tools such as GIS mapping and ESG reporting.

Conclusion

India’s urban future will be determined not by a single policy or technological advance, but by the convergence of three interdependent forces: circularity, small-town development, and behavioural change. Circularity provides a framework for rethinking about how resources are used, reused, and recycled. Small towns, where significant new urban growth is occurring, represent important locations where these circular patterns can be nurtured and measured before unstable patterns take root. And changes in behavior ensure that these models transcend policy documents and are incorporated into the daily lives and attitudes of citizens.

Taken together, these three aspects pave the way for a new approach to sustainable urban development in India – one that is resilient, inclusive, and future-ready. Circularity ensures environmental responsibility, promotes sustainability beyond the confines of megacities by developing smaller towns, and behavioral change supports a complete transition to community participation and ownership.

The challenge ahead is to forge these threads into a coherent national and local agenda where policies are realistic, communities are engaged, and development is guided by long-term ecological balance rather than short-term gains. If India succeeds in combining these forces, its cities, both large and small, can emerge not as symbols of crisis, but as models of sustainability, innovation, and shared prosperity.

Sn. Researcher

Watershed Organisation Trust (WOTR), Pune