Abstract

The global textile industry generates substantial waste across production, pre-consumer, and post-consumer stages, contributing to greenhouse gas emissions, resource depletion, and pollution. Transitioning to a circular economy (CE) offers a pathway to mitigate these impacts by closing material loops, extending product lifespans, and promoting resource recovery. This study synthesises recent literature to examine waste streams, recycling technologies, and the barriers, drivers, and opportunities shaping CE adoption in textile waste management. The analysis identifies persistent technological challenges such as mixed fibre compositions and limited composite recycling alongside economic constraints, policy gaps, and low consumer participation. At the same time, regulatory momentum, technological innovation, and emerging circular business models present opportunities for large-scale adoption. A five-pillar strategic framework is proposed, integrating technological scaling, policy alignment, market development, capacity building, and consumer engagement. This integrated approach emphasises the need for harmonised Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) schemes, guaranteed offtake agreements, decentralised sorting hubs, and targeted R&D in under-served waste streams like technical textiles and composites. Findings suggest that coordinated action among stakeholders, supported by financial incentives and behavioural change strategies, is essential for achieving a sustainable circular textile economy. The framework provides researchers, industry leaders, and policymakers with practical strategies to support the transition of textile waste management from a linear model to a more circular system.

Keywords

“Circular economy, Textile waste management, Recycling technologies, Sustainable textiles, Policy and governance”

1. Introduction

The global fashion and textile industry generates more than 100 million tonnes of waste each year, making it a significant contributor to environmental degradation. Much of this waste is either incinerated or disposed of in landfills, practices that accelerate pollution, deplete valuable resources, and release large volumes of greenhouse gases (Niinimäki et al., 2020; Papamichael et al., 2023). The rise of fast fashion has intensified these problems by promoting rapid product turnover and reducing the average lifespan of garments (Shamsuzzaman et al., 2025).

In response, the principles of the circular economy (CE) offer a restorative alternative. By prioritizing practices such as resource recovery, recycling, remanufacturing, reuse, and repair, the CE seeks to maximize material utility while minimizing waste (Kirchherr et al., 2017; Papamichael et al., 2023). The adoption of CE models not only reduces reliance on virgin resources but also mitigates environmental pressures and opens new economic opportunities (Geissdoerfer et al., 2017; Dissanayake & Sinha, 2015).

Nevertheless, the transition to circular textile systems faces persistent challenges. Consumer behavior, market volatility, fragmented policy frameworks, and technological limitations remain substantial barriers (Shirvanimoghaddam et al., 2020; Tura et al., 2019; Shamsuzzaman et al., 2025). Addressing these obstacles requires coordinated action among stakeholders, investment in advanced recycling technologies, and the establishment of robust governance mechanisms (Mahdi et al., 2021; European Commission, 2022). Against this backdrop, the present study explores the opportunities, constraints, and enabling factors within the CE landscape, and proposes a strategic framework to accelerate circular textile waste management.

2. Literature Review

The application of circular economy (CE) principles in textiles focuses on systemic redesign, product longevity, and closed material loops (Kirchherr et al., 2017; Geissdoerfer et al., 2017). In practice, this translates into designing for recyclability, improving production efficiency, and advancing recovery strategies that retain material value (Dissanayake & Sinha, 2015; Papamichael et al., 2023).

Global textile waste continues to rise, driven by fast fashion and shortened garment lifespans. Fewer than 20% of discarded textiles are recycled, with most landfilled or incinerated, leading to microplastic release, toxic leachate, and greenhouse gas emissions (Niinimäki et al., 2020; Sandin & Peters, 2018; Papamichael et al., 2023).

Recycling technologies offer mixed progress. Mechanical methods are low-cost but limited by contamination and fibre weakening (Shirvanimoghaddam et al., 2020; Xie et al., 2021). Chemical recycling enables fibre-to-fibre recovery from blends but is capital intensive and complex (Mahdi et al., 2021). Biological processes remain promising yet early-stage (Payne, 2015; Papamichael et al., 2023). Policy instruments such as Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR), eco-design standards, and bans on destroying unsold goods have advanced CE adoption in the EU (European Commission, 2022; Watson et al., 2020). However, weak standards and enforcement in many developing economies constrain impact (Tura et al., 2019; Shamsuzzaman et al., 2025).

Behavioural and market barriers further slow adoption. Consumers show low participation in take-back schemes due to price sensitivity, convenience, and awareness gaps (Niinimäki et al., 2020; Papamichael et al., 2023). On the supply side, volatile demand for recycled fibres and absent offtake agreements discourage investment (Krauklis et al., 2021; Shamsuzzaman et al., 2025).

Despite extensive research on CE principles and recycling technologies, few studies integrate technological, policy, and behavioural perspectives. Moreover, technical textiles and composites remain underexplored despite their growing environmental relevance (Krauklis et al., 2021; Papamichael et al., 2023).

3. Methodology

This study adopts a systematic literature review (SLR) approach to synthesise existing research on textile waste management within the circular economy (CE) framework. The method ensures a comprehensive and transparent analysis by following a structured process for identification, selection, and synthesis of relevant sources (Shamsuzzaman et al., 2025; Papamichael et al., 2023).

3.1 Search strategy and selection criteria

Academic databases including Scopus, Web of Science, and ScienceDirect were searched using keywords such as “textile waste management”, “circular economy”, “recycling technologies”, and “sustainable textiles”. Studies published between 2010 and 2025 were considered, with a focus on peer-reviewed journal articles, industry reports, and policy documents.

The inclusion criteria were:

Direct relevance to textile waste management in the context of CE.

Coverage of at least one thematic technological, policy, market, or behavioural aspect.

Availability of full text in English.

Exclusion criteria were:

Studies unrelated to textiles or CE.

Conference abstracts without full papers.

Non-English sources.

3.2 Data extraction, synthesis, and analytical framework

The selected studies were coded and thematically analysed to capture patterns in waste generation, recycling technologies, policy frameworks, market dynamics, and behavioural aspects. Manual coding ensured contextual accuracy, with data management tools used to maintain an audit trail (Shamsuzzaman et al., 2025; Papamichael et al., 2023). To complement this, a descriptive statistical overview mapped the distribution of research themes, geographic focus, and methodological approaches. This combined strategy highlighted critical gaps, especially in linking technological, policy, and behavioural dimensions of textile waste management (Shamsuzzaman et al., 2025).

4. Waste Streams and Their Environmental Impacts

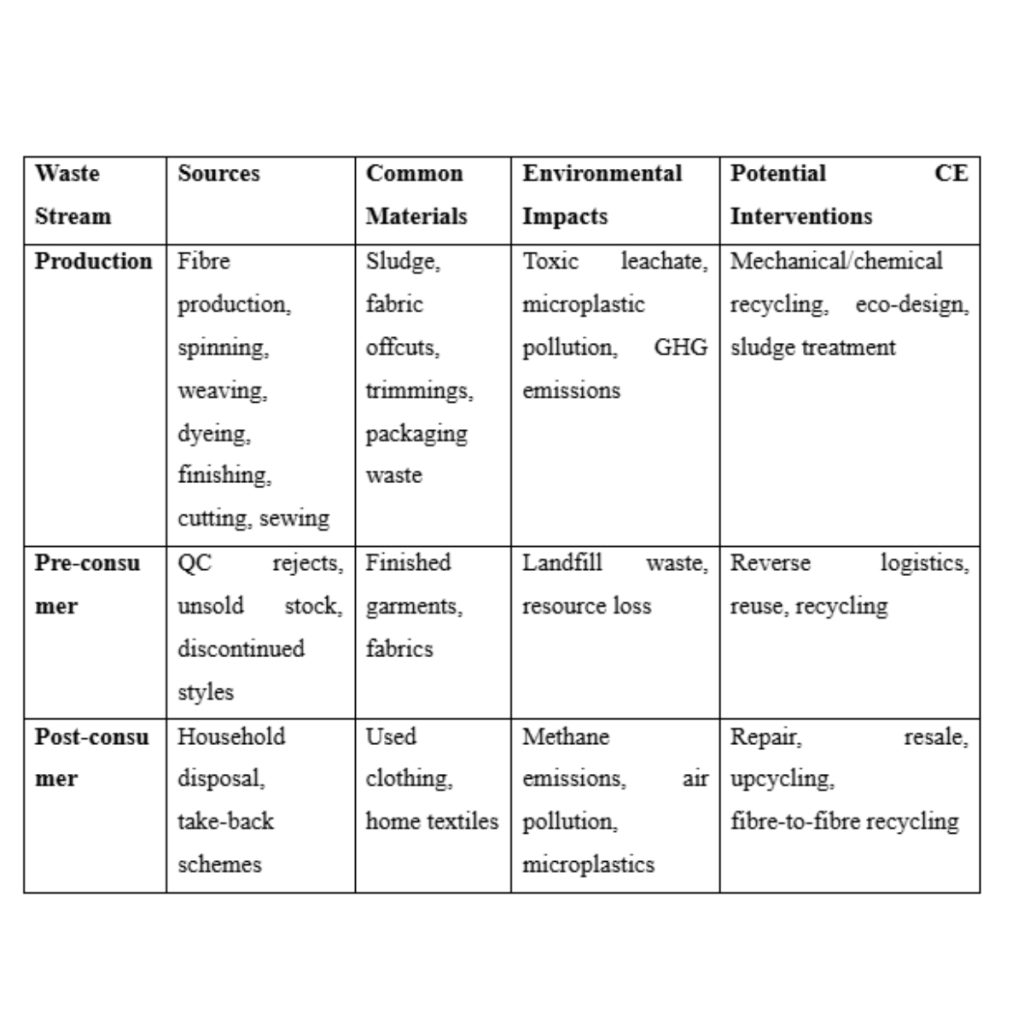

Textile waste is generated throughout the value chain, from fibre production to end-of-life disposal, and can be categorised into production waste, pre-consumer waste, and post-consumer waste (Nyika and Dinka, 2022; Papamichael et al., 2023; Shamsuzzaman et al., 2025). Each waste stream presents distinct challenges for collection, treatment, and recycling, with associated environmental consequences.

4.1 Production waste

Production waste includes fibre sweepings, fabric offcuts, selvages, trimmings, and defective parts generated during spinning, weaving, dyeing, finishing, cutting, and sewing operations (Nyika and Dinka, 2022; Kant, 2012). Wastewater sludge from dyeing and finishing processes often contains toxic dyes, heavy metals, and auxiliaries, which contribute to soil and water contamination if inadequately treated (Kant, 2012; Muthu, 2020).

4.2 Pre-consumer waste

Pre-consumer waste arises from unsold stock, quality control rejects, and style discontinuations before products reach consumers (Dissanayake and Sinha, 2015; Papamichael et al., 2023). Brand protection policies sometimes lead to incineration or shredding of unsold goods, while limited reverse logistics capabilities prevent reuse or recycling at scale (Watson et al., 2020; Shamsuzzaman et al., 2025).

4.3 Post-consumer waste

Post-consumer waste consists of garments and household textiles discarded after use. Globally, less than 20% of post-consumer textiles are collected for reuse or recycling, with the majority ending up in landfills or incinerators (Papamichael et al., 2023; Niinimäki et al., 2020). Landfilled natural fibres release methane as they decompose, while synthetic textiles contribute to microplastic pollution (Belzagui et al., 2019; Muthu, 2020).

4.4 Environmental impacts

- Water pollution: Dye sludge and process effluents containing heavy metals and organic compounds can contaminate surface and groundwater (Kant, 2012; Muthu, 2020).

- Greenhouse gas emissions: Incineration of synthetic textiles releases CO₂, nitrous oxide, and other harmful emissions (Papamichael et al., 2023; Belzagui et al., 2019).

- Resource depletion: Discarded textiles represent embedded water, energy, and raw materials that are permanently lost if unrecovered (Niinimäki et al., 2020; Shamsuzzaman et al., 2025).

- Land use pressure: Landfilling consumes valuable space and can cause soil contamination (Nyika and Dinka, 2022; Muthu, 2020).

5. Recycling Technologies in the CE Context

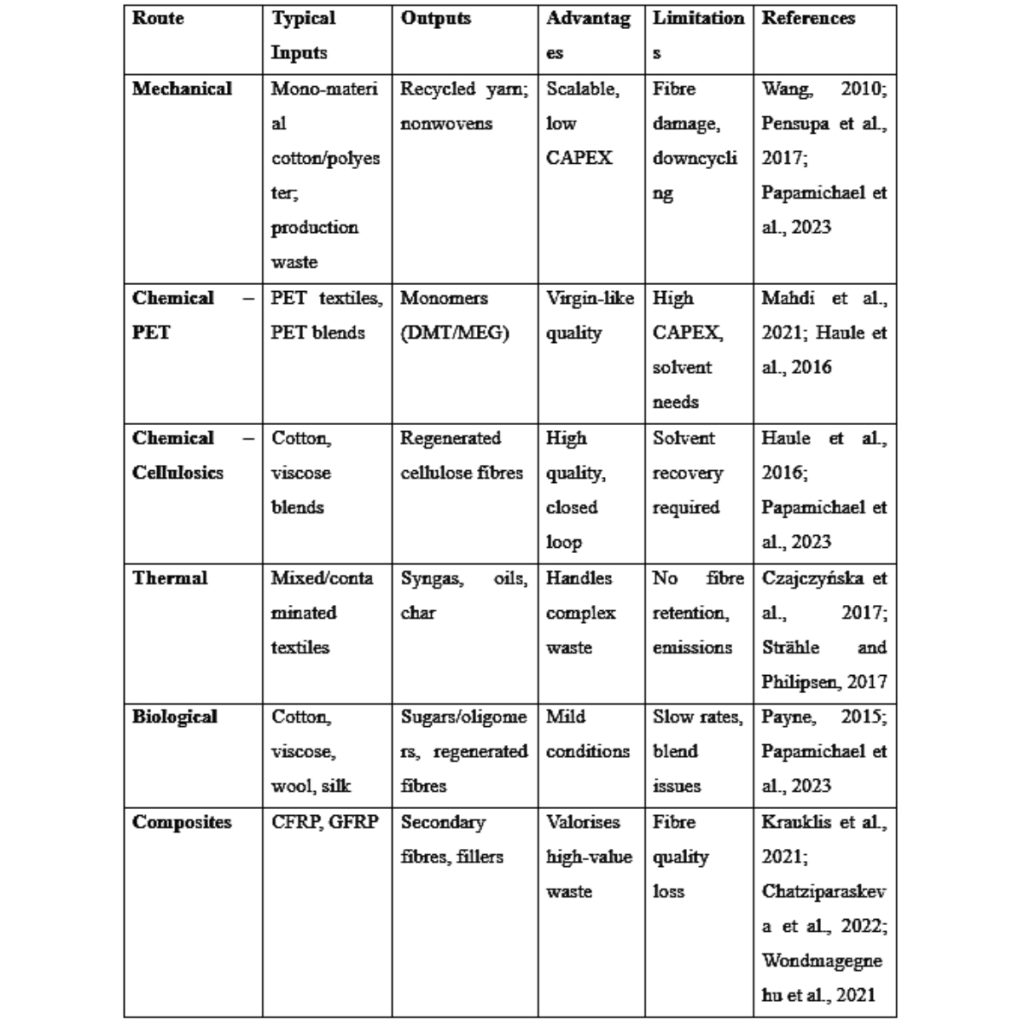

Recycling technologies for textiles can be categorised into mechanical, chemical, thermal, and emerging biological processes, with a growing focus on specialised methods for technical textiles and fibre-reinforced composites. Each pathway differs in feedstock compatibility, output quality, technological readiness, and environmental trade-offs (Papamichael et al., 2023; Shirvanimoghaddam et al., 2020; Shamsuzzaman et al., 2025).

5.1 Mechanical recycling

Mechanical recycling involves processes such as cutting, shredding, carding, and re-spinning, commonly applied to mono-material textiles and clean production waste (Wang, 2010; Pensupa et al., 2017). While cost-effective and well-established, it results in fibre shortening and quality loss, leading to downcycling into nonwoven products, insulation, or wiping cloths (Shirvanimoghaddam et al., 2020; Papamichael et al., 2023A common strategy for increasing yarn strength is to blend recovered cotton with virgin polyester (Pensupa et al., 2017).

5.2 Chemical recycling

Depolymerization for synthetic fibers, solvent-based separation for cellulosics, and hydrolysis/glycolysis procedures are examples of chemical recycling (Haule et al., 2016; Mahdi et al., 2021). These techniques can handle mixed materials and create virgin-equivalent fibers, but they come with significant operating and capital costs and need high feedstock purity (Papamichael et al., 2023; Shamsuzzaman et al., 2025). To lessen environmental effects, green chemistry techniques and efficient solvent recovery are crucial (Mahdi et al., 2021).

5.3 Thermal recycling and energy recovery

Thermal methods such as pyrolysis and gasification convert textiles into syngas, oils, and char, offering a solution for contaminated or complex material streams (Czajczyńska et al., 2017; Strähle and Philipsen, 2017). However, these processes do not maintain fibre loops and require robust emission control systems (Papamichael et al., 2023; Shamsuzzaman et al., 2025).

5.4 Biological recycling (emerging)

Biological methods use enzymatic or microbial processes to break down natural fibres such as cotton, viscose, wool, and silk under mild conditions (Payne, 2015; Papamichael et al., 2023). While potentially reducing energy and chemical requirements, current limitations include slow reaction rates and challenges in processing blended materials.

5.5 Technical textiles and fibre-reinforced composites End-of-life management for composites (e.g., carbon or glass fibre reinforced polymers) remains underdeveloped, with current options focusing on mechanical size reduction or pyrolysis, often with loss of fibre quality (Krauklis et al., 2021; Chatziparaskeva et al., 2022). Solvolysis offers higher-quality fibre recovery but faces cost and solvent recovery challenges (Mativenga et al., 2017; Wondmagegnehu et al., 2021).

6. Barriers, Drivers, and Opportunities

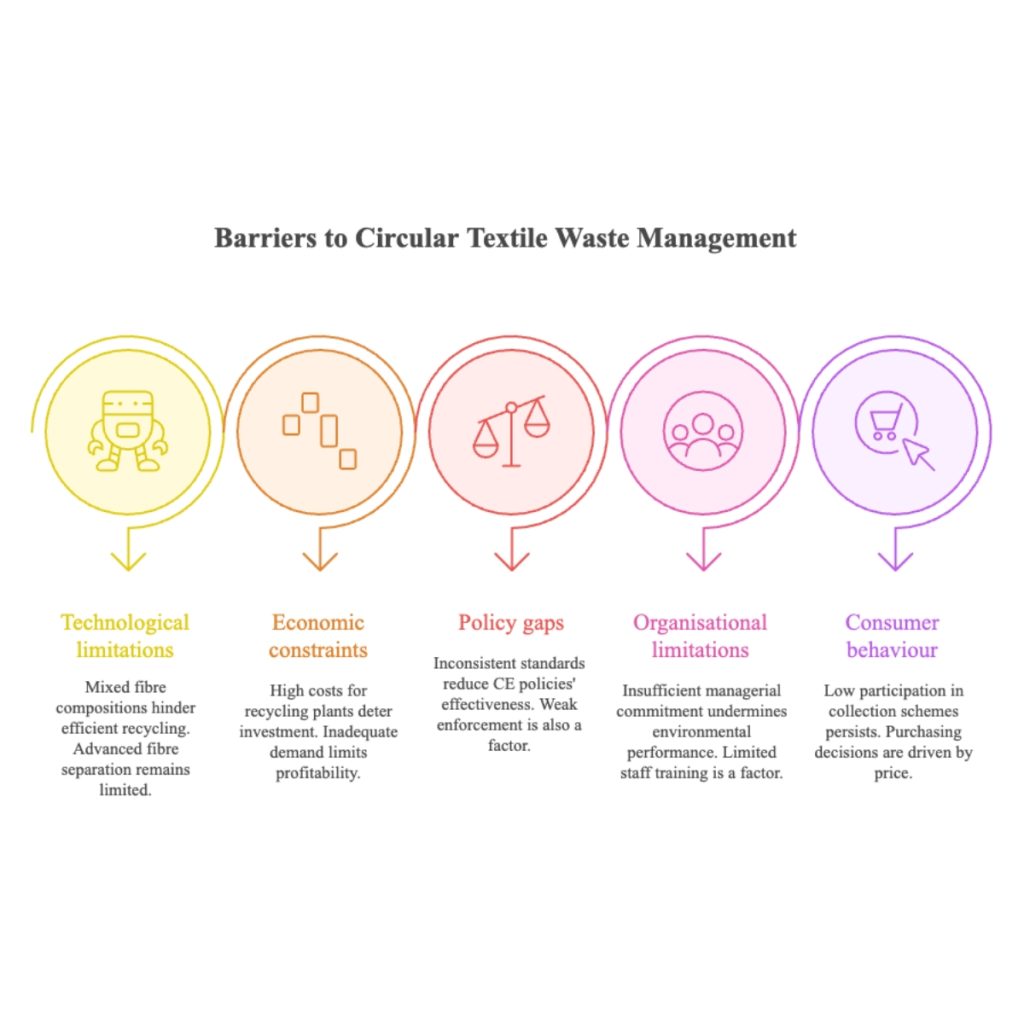

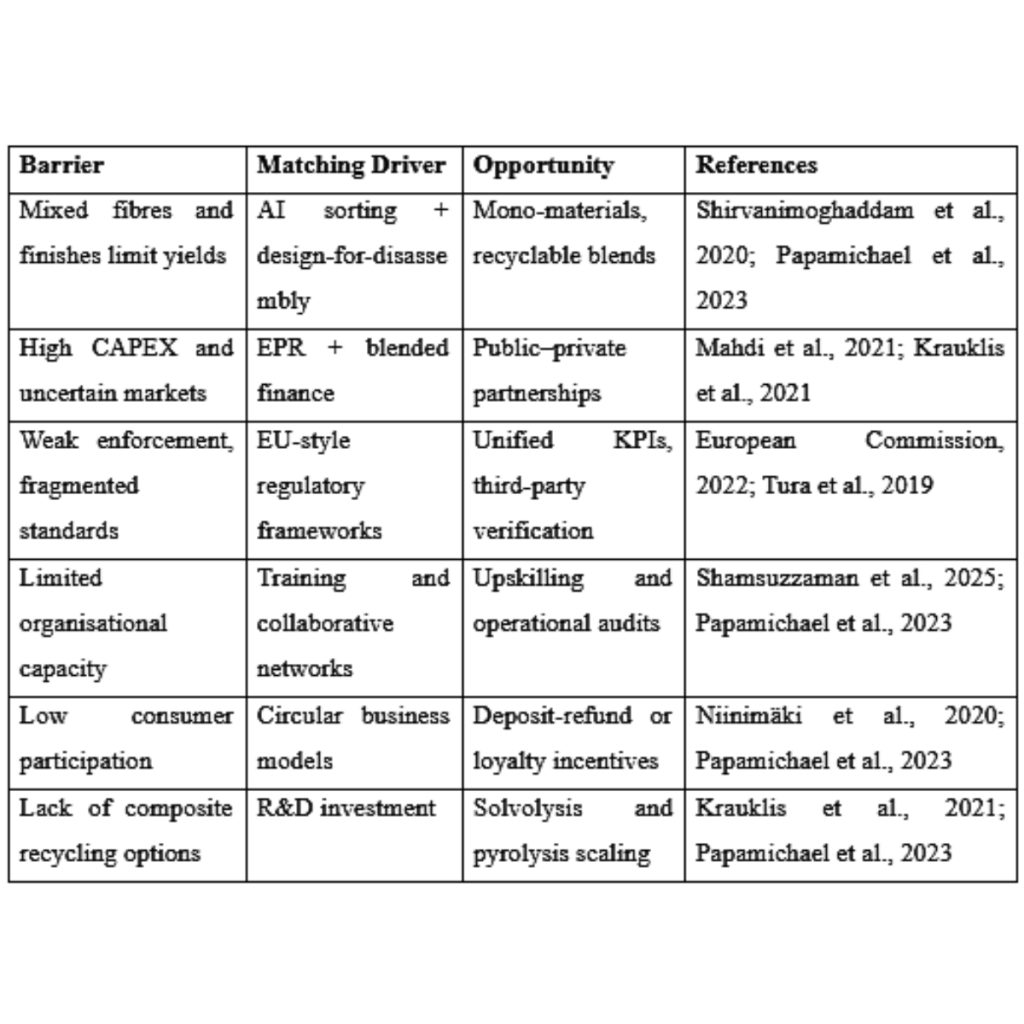

Adoption of circular economy (CE) principles in textile waste management is influenced by interlinked technological, economic, policy, organisational, and behavioural factors. Evidence from recent studies highlights that while policy frameworks and technological advances are gaining traction, structural challenges continue to impede large-scale implementation (Papamichael et al., 2023; Shamsuzzaman et al., 2025).

6.1 Barriers

Technological and infrastructural limitations.

Mixed fibre compositions, elastane content, and chemical finishes hinder efficient recycling, reducing both yield and quality. Advanced fibre separation and automated sorting remain limited in many regions, particularly in developing economies (Shirvanimoghaddam et al., 2020; Mahdi et al., 2021; Shamsuzzaman et al., 2025). Biological recycling, while promising, faces challenges in reaction rates, blend selectivity, and industrial scalability (Payne, 2015; Papamichael et al., 2023).

Economic and market constraints.

High investment and operational costs for chemical recycling plants, coupled with volatile secondary material markets, deter investment. Inadequate demand for recycled fibres, especially in technical textiles and composites, further limits profitability (Mahdi et al., 2021; Krauklis et al., 2021; Shamsuzzaman et al., 2025).

Policy and governance gaps.

Inconsistent standards, weak enforcement, and lack of harmonised Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) schemes reduce the effectiveness of CE policies in emerging economies (Tura et al., 2019; European Commission, 2022; Shamsuzzaman et al., 2025).

Organisational capacity limitations.

Insufficient managerial commitment, limited staff training, and gaps in operational control such as inadequate monitoring in effluent treatment plants undermine environmental performance (Shamsuzzaman et al., 2025; Papamichael et al., 2023).

Consumer behaviour.

Low participation in collection and take-back schemes persists, with purchasing decisions still largely driven by price, convenience, and style over sustainability considerations (Niinimäki et al., 2020; Papamichael et al., 2023).

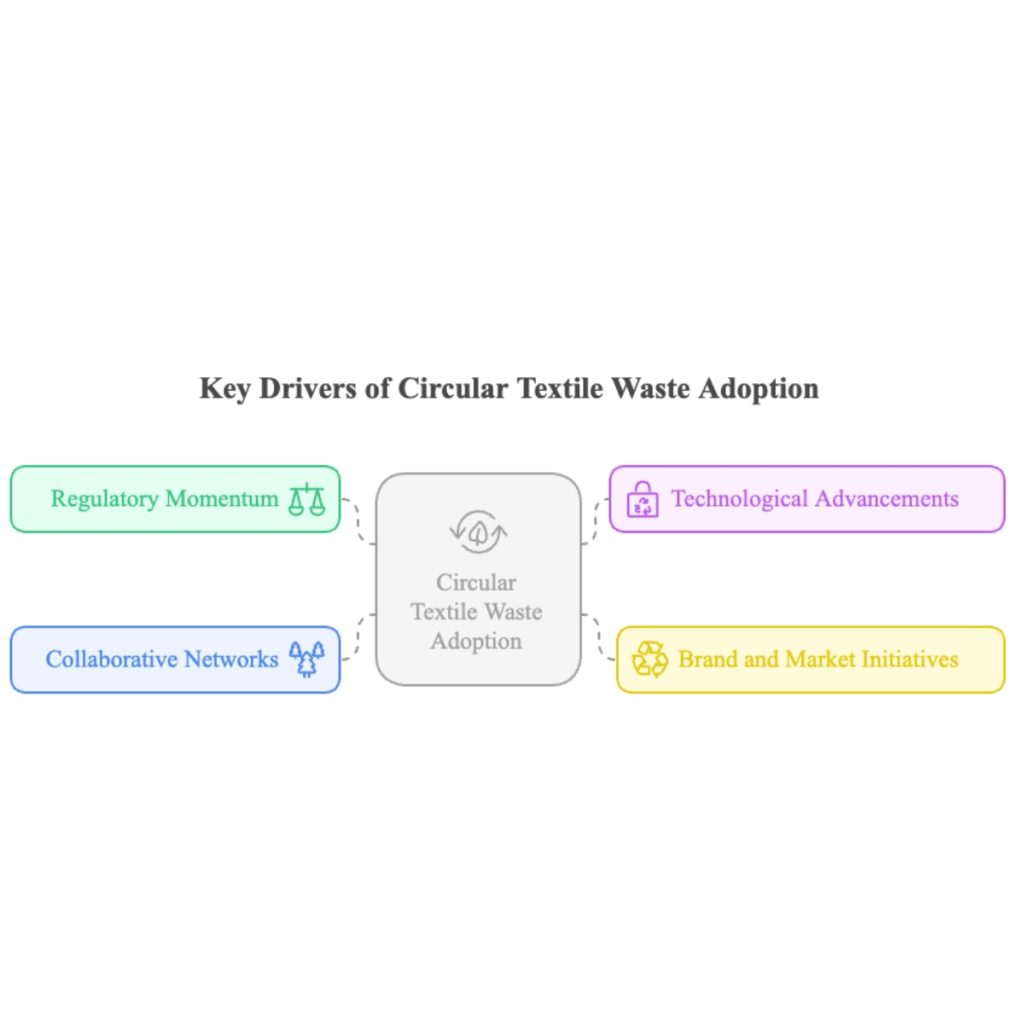

6.2 Drivers

Regulatory momentum: The EU Strategy for Sustainable and Circular Textiles mandates eco-design requirements, digital product passports, and bans on the destruction of unsold goods, setting a global benchmark for policy design (European Commission, 2022; Watson et al., 2020). EPR pilots have shown potential to encourage design-for-recycling and improve collection rates (Tura et al., 2019).

Technological advancements: Deployment of AI-enabled sorting, IoT-based waste tracking, and blockchain-enabled traceability has improved feedstock quality and supply chain transparency (Kumar et al., 2021; Xie et al., 2021). Chemical recycling technologies capable of handling blended textiles are becoming more viable with better pre-sorting and green chemistry processes (Mahdi et al., 2021; Papamichael et al., 2023).

Brand and market initiatives: Circular business modelssuch as garment take-back, resale, and rentalare expanding globally. These models, when integrated with logistics partners, enhance collection volumes and build secondary markets (Papamichael et al., 2023; Shamsuzzaman et al., 2025).

Collaborative networks: Partnerships between brands, recyclers, municipalities, and NGOs facilitate knowledge sharing, risk reduction, and faster technology adoption (Shamsuzzaman et al., 2025; Papamichael et al., 2023).

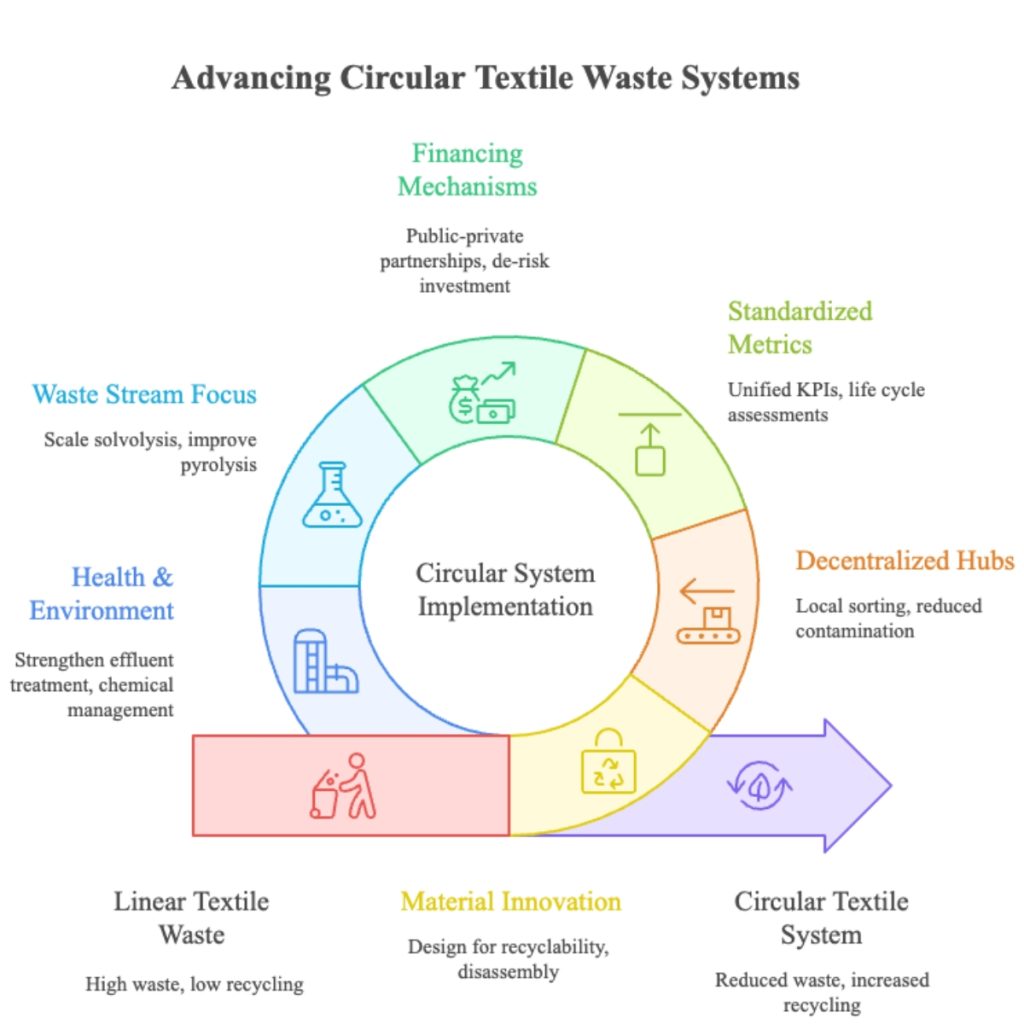

6.3 Opportunities

Material and product innovation. Mono-material textiles, recyclable blends, and design-for-disassembly can significantly improve recyclability and fibre recovery rates (Dissanayake and Sinha, 2015; Papamichael et al., 2023).

Decentralised processing hubs. Local pre-sorting facilities reduce contamination and transport emissions, making recycling more economically viable (Nyika and Dinka, 2022; Shamsuzzaman et al., 2025).

Standardised metrics and transparency. Adoption of unified KPIs, regular life cycle assessments, and third-party verification can increase consumer trust and comparability across markets (Papamichael et al., 2023; Tura et al., 2019).

Financing mechanisms. Blended finance models and targeted public–private partnerships can de-risk investment in recycling technologies and infrastructure (Shamsuzzaman et al., 2025; Krauklis et al., 2021).

Under-addressed waste streams. Technical textiles and composites represent a growing challenge; scaling solvolysis and improved pyrolysis could enable higher-quality secondary materials (Krauklis et al., 2021; Papamichael et al., 2023).

Health and environmental co-benefits. Strengthening effluent treatment and chemical management reduces environmental pollution and improves worker and community health (Kant, 2012; Shamsuzzaman et al., 2025).

.

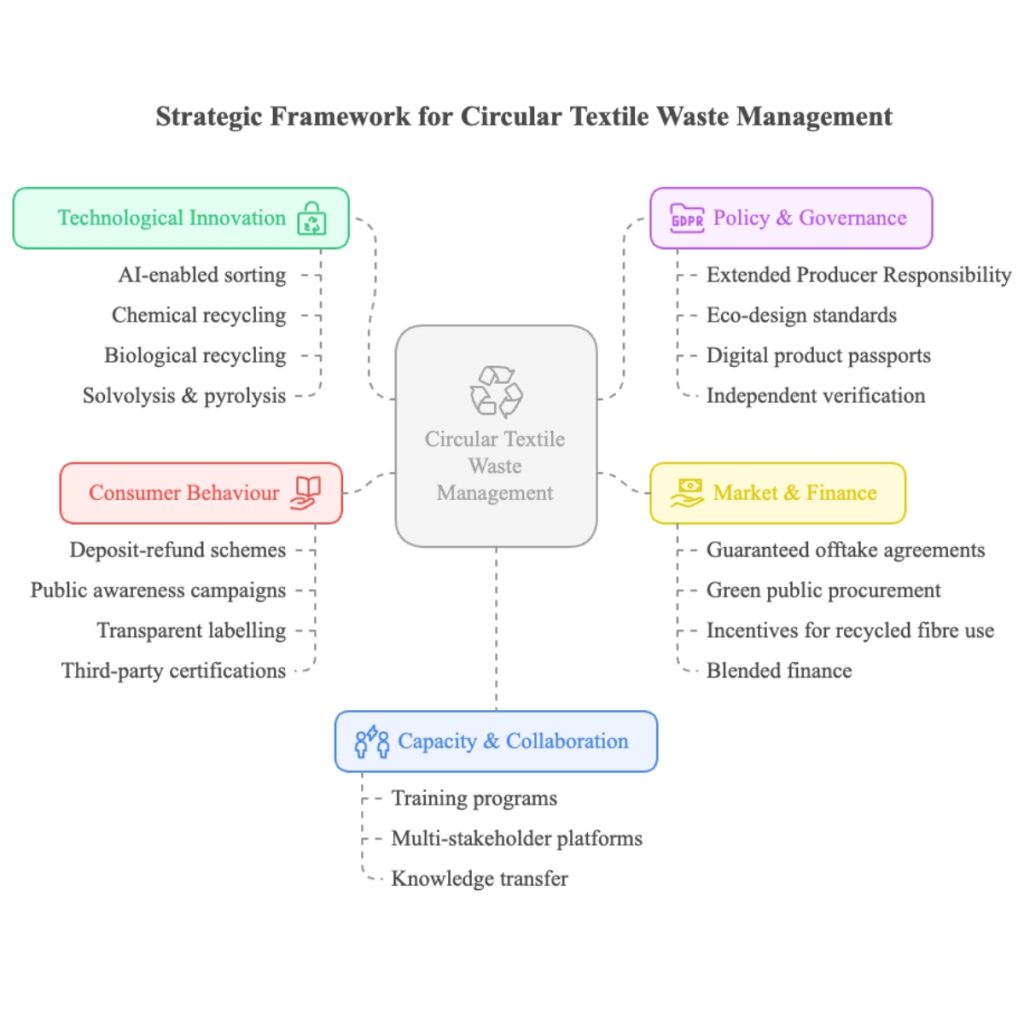

7. Strategic Framework for Advancing Circular Textile Waste Management

A successful transition to circular textile waste management requires an integrated framework that aligns technology, policy, markets, skills, and consumer behaviour (Papamichael et al., 2023; Shamsuzzaman et al., 2025).

On the technological front, priority investments include AI-enabled sorting, chemical recycling for blended fabrics, and emerging biological processes. Specialised methods for technical textiles—such as solvolysis and pyrolysis—also need targeted R&D and pilot-scale support (Mahdi et al., 2021; Krauklis et al., 2021; Chatziparaskeva et al., 2022). Policy measures must work in tandem, with harmonised Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR), eco-design standards, and digital product passports helping to standardise requirements across markets. Effective governance will also require clear metrics, independent verification, and penalties for non-compliance (European Commission, 2022; Watson et al., 2020; Tura et al., 2019).

Market stability can be fostered through guaranteed offtake agreements, green public procurement, and financial incentives for recycled fibres. Blended finance models—combining public subsidies, concessional lending, and private capital—can further de-risk large infrastructure investments (Papamichael et al., 2023; Shamsuzzaman et al., 2025). Strengthening capacity is equally critical, particularly through training for plant operators, inspectors, and designers, alongside multi-stakeholder platforms that facilitate technology transfer and knowledge exchange. Finally, behavioural change remains a cornerstone of CE adoption. Public campaigns, deposit-refund systems, and retailer-led take-back schemes can drive participation, while transparent labelling and third-party certifications build consumer trust and combat greenwashing (Niinimäki et al., 2020; Papamichael et al., 2023).

8. Discussion

The findings emphasise that transitioning to a circular textile waste management system requires systemic change rather than incremental adjustments. Current recycling technologies, while advancing, remain insufficient to address blended fibres, elastane-rich fabrics, and technical composites (Shirvanimoghaddam et al., 2020; Mahdi et al., 2021; Krauklis et al., 2021).

Technological solutions such as AI-based sorting, solvent recovery, and decentralised pre-sorting hubs can enhance recovery rates, but without aligned policies—including Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR), eco-design standards, and recycled content targets—economic viability is limited (European Commission, 2022; Watson et al., 2020). Similarly, financial barriers persist due to volatile secondary fibre markets and high capital costs, which could be mitigated through blended finance models and guaranteed offtake agreements (Mahdi et al., 2021; Shamsuzzaman et al., 2025).

Collaboration among brands, recyclers, NGOs, municipalities, and research institutions is vital to accelerate CE adoption, supported by capacity-building programmes for operators, inspectors, and designers (Papamichael et al., 2023; Shamsuzzaman et al., 2025). At the consumer level, low participation in take-back schemes highlights the need for economic incentives such as deposit-refund systems, loyalty rewards, and transparent labelling to build trust and counter greenwashing (Niinimäki et al., 2020; Tura et al., 2019).

Finally, unaddressed waste streams such as technical textiles and composites represent a frontier for innovation. Expanding solvolysis and pyrolysis, along with hybrid recycling technologies, could deliver significant sustainability benefits if coupled with coordinated R&D and supportive market incentives (Krauklis et al., 2021; Chatziparaskeva et al., 2022)

.9. Conclusion

The transition to circular textile waste management is essential for reducing environmental impacts, conserving resources, and building sustainable value chains. This study reviews recent research to identify the main barriers, opportunities, and motivators, focusing on technological readiness, policy alignment, market mechanisms, and stakeholder engagement.

Emerging solutions such as chemical recycling of blends, biological recovery processes, and AI-enabled sorting hold promise for closing material loops. However, in the absence of standardized frameworks such as Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) schemes and eco-design requirements their impact remains constrained. Market development through blended finance and offtake agreements can stabilize demand for recycled fibres while lowering investment risk. At the same time, collaboration, capacity building, and consumer participation facilitated by deposit-refund schemes, transparent labelling, and third-party certification are critical to scaling adoption. Technical textiles and composites represent an underutilized waste stream and a frontier for innovation requiring targeted R&D investment.

Overall, a strategically integrated approach that combines innovation, coherent policy, market incentives, and behavioural change can accelerate the shift to a circular textile industry while creating new economic opportunities.

Ph.D. Scholar NIFT

New Delhi

Professor of Fashion Technology NIFT

New Delhi