Currently, this decade has witnessed a transformative shift in how urban centres address waste, moving beyond conventional disposal methods towards holistic, circular solutions. Despite widespread awareness of waste management issues, cities still grapple with mounting waste and dwindling resources, exposing the limitations of linear disposal systems. In response, policy frameworks, such as the Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), play a crucial role in regulating urban systems and steering them towards circularity. These frameworks are nudging companies to optimise their supply chain to minimise waste and maximise resource efficiency. Cities, accounting for 75% of global resource consumption and nearly 80% of greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs), still operate predominantly on a linear system where the materials enter as resources and exit as waste. However, by adopting cradle-to-cradle (C2C) principles, urban areas hold the potential not just to mitigate the environmental burden of waste, but to build regenerative systems that prioritise reuse, redesign, and long-term sustainability.

Understanding Cradle-to-Cradle Approach

What if waste was never the end, but part of a cycle?

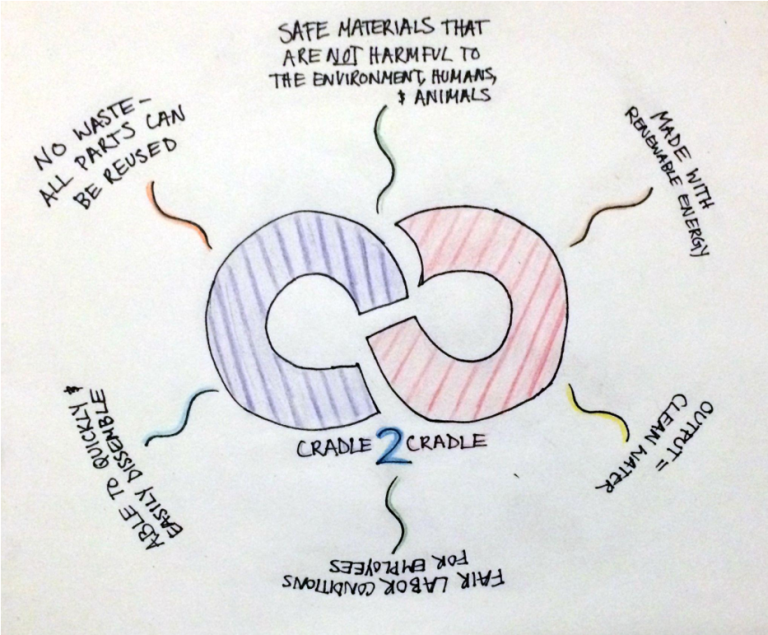

This question forms the foundation of the Cradle-to-Cradle (C2C) approach — a framework that challenges the long-standing linear model of take-make-dispose. Introduced in 2002 by architect Willian McDonough and chemist Michael Braungart, the C2C reimagines materials not as single-use consumables, but as resources designed to flow in perpetual cycles.

Though traditional recycling has long served in diverting waste from landfills, C2C promotes a “closed-loop” system by keeping materials in circulation and retaining their value across multiple life cycles. Here, the materials are intentionally selected to either safely return to the environment through biological cycles (such as compostable packaging or biodegradable polymers) or be endlessly recovered through technical cycles (such as high-grade plastics or metals in closed-loop recovery systems), helping cities design out waste rather than manage it at the end.

Rethinking the Journey of Urban Waste

To integrate circularity in cities, it is essential to understand the current trajectory of urban waste that often ends in ways far from ideal. Waste typically originates from households, markets, and industries before being collected and transported to landfills or dumpsites. Unfortunately, we continue to witness heaps of waste in poorly managed dumps, thereby compounding urban pollution and accelerating climate change.

In many urban areas, the “afterlife” of plastics is particularly alarming. We know for a fact that plastics do not decompose naturally, unlike biodegradable materials. Rather, they persist in the environment for centuries and often end up in mixed municipal waste streams, rendering them nearly impossible to recover. Over time, this non-segregated plastic breaks down into microplastics that contaminate soil, water, and even the air, posing a grave threat to both terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems. According to the OECD (2022), only 9% of all plastic waste has ever been successfully recycled, while 22% is mismanaged and directly pollutes the marine environment.

Especially in developing countries, as the cities expand, construction and demolition (C&D) waste has resulted in surging volumes of construction debris such as concrete, bricks, wood, glass, metals, and tiles. With limited infrastructure to process such bulk waste, C&D debris is frequently dumped illegally in wetlands, abandoned plots, or on roadsides. The lack of regulatory enforcement leads to the irreversible loss of reusable materials, increasing demand for virgin materials and the carbon footprint of new construction.

E-waste, or discarded electronic and electrical equipment, is the fastest-growing solid waste stream globally. This e-waste is dumped alongside household waste, where its valuable components, such as gold, copper, and palladium, still remain unrecovered. More dangerously, its toxic constituents like lead, cadmium, and brominated flame retardants leach into soil and groundwater, posing severe health risks to nearby populations. According to the Global E-waste Monitor (2024), only 22.3% of global e-waste is recycled through official channels, with the rest contributing to hidden pollution burdens in urban environments.

Why Policies Matter in Building Circular Urban Waste Systems

Managing urban waste is no longer just an environmental concern but a prerequisite for building circularity in cities and sustainable economies. As white pollution continues to rise, the costs of inaction, which are climate risks, resource depletion, and socio-economic marginalisation, grow steeper. Globally and within India, adaptive and enforceable policies are key to restructuring how we manage waste, enabling a shift from a linear disposal model to one of resource regeneration.

1. Structuring Circular Waste Governance

Policies act as the blueprint for organising waste management from end to end. For instance, in South Korea, a mandatory Volume-Based Waste Fee (VBWF) system requires residents to purchase designated waste bags priced according to their size—the larger the bag, the higher the cost. Recyclable materials are collected separately in designated bins free of charge, encouraging proper segregation and recovery. This fee structure creates a strong financial incentive for residents to reduce waste generation and increase recycling rates.

Similarly, urban policies in India mandating multi-stream segregation systems (4 or 8 ways) have demonstrated enhanced quality of material, and less landfilling, through improved organising to effect and facilitate the traceability of recyclable material, less cross-contamination, and greater value of recyclates in a circular economy by improving material circularity and resource efficiency.

2. Institutionalising Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR)

Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) enables manufacturers, processors, and distributors to actively engage in managing the environmental footprint of their products beyond the point of sale. By aligning compliance with circular practices, EPR helps businesses to invest in eco-design, reduce material complexity, and shift towards recyclable or reusable packaging. India’s EPR mandates define specific targets for collection, recycling, and reuse, supported by digital traceability and reverse logistics. These policies also establish structured coordination and accountability across the value chain through shared platforms that connect brand owners, Urban Local Bodies (ULBs), and Producer Responsibility Organisations (PROs).

A notable example is Hindustan Unilever, which has partnered with PROs to collect and recycle post-consumer plastic packaging across multiple Indian states, exceeding their annual EPR targets. Internationally, France’s “polluter pays” model similarly funds public systems and eco-innovation, while encouraging investment in decentralised infrastructure and informal worker inclusion. Ultimately, EPR-driven frameworks promote eco-design, strengthen secondary markets, and integrate circularity into product development and waste governance.

3. Scaling Infrastructure and Technology Upgrades

A circular economy cannot function without the right infrastructure in place. Over the years, policies have increasingly mandated decentralised facilities like Material Recovery Facilities (MRFs) and Dry Waste Collection Centres (DWCCs) as integral components of urban waste management.

MRFs are designed to receive dry waste that is either source-segregated or preliminarily sorted. These facilities further segregate materials into specific categories, enabling higher recovery value. They bridge the gap between collection and recycling by preparing recyclables for re-entry into the circular loop. DWCCs, on the other hand, serve as primary drop-off or collection centres for non-biodegradable waste collected by municipal workers or informal waste pickers. This enables basic segregation and helps channel materials toward MRFs or recycling vendors, reducing landfill dependency and enhancing material circularity.

In India, regulatory frameworks under the Swachh Bharat Mission (SBM) now promote city-level planning for such infrastructure, backed by fiscal support and viability gap funding. At the same time, policies are encouraging digital tools like GIS mapping and real-time monitoring to improve traceability, reduce leakages, and strengthen system efficiency across the waste value chain.

4. Driving Behavioural Change and Community Engagement

In India, the Swachh Bharat Mission (SBM) has made Information, Education and Communication (IEC) campaigns a non-negotiable component of waste management plans. These policies have encouraged local bodies to design community-led programmes, from school-based activities to neighbourhood awareness drives. In some parts of the country, Self-Help Groups (SHGs) and Resident Welfare Associations (RWAs) have also been mobilised to lead by example.

Globally, countries like South Korea have paired a Garbage Separation Policy, which mandates strict segregation of waste into recyclables, food waste, and general waste, and is reinforced by regular community education, school programmes, public campaigns, and feedback systems. As a result, citizens are not only aware of their responsibilities but are also empowered and incentivised to participate in the waste management system

5. Creating a Market for Secondary Plastics

Creating demand for recycled plastics is key to introducing circularity in cities, and this is where supportive policies have begun to make a real difference. In India, recent guidelines now mandate a minimum percentage of recycled content in certain plastic products, such as carry bags and rigid packaging used in the FMCG and e-commerce sectors.

For instance, the Plastic Waste Management Rules (Amendment), 2022 require producers to incorporate recycled plastic in packaging across specified categories over a phased timeline, nudging manufacturers to reduce reliance on virgin polymers. These measures are encouraging innovation in reprocessing technologies and creating new opportunities for MSMEs in the recycling space. By formalising this segment and providing clearer demand signals, such policies help anchor circularity deeper within manufacturing systems and long-term waste governance.

6. Enabling Public-Private Partnerships (PPP) for Circularity

To scale sustainable waste management systems, models like concession agreements and performance-linked contracts have created a more predictable framework for private sector participation. By offering viability gap funding, technical assistance, and co-investment models, governments are actively de-risking waste sector projects.

At the same time, circularity is not viewed solely through an environmental lens. In UNEP’s Global Waste Management Outlook, a circular economy must also be socially inclusive, recognising the contributions of all stakeholders, especially those on the margins. The International Labour Organisation (ILO) further emphasises that the transition to circular systems presents a unique opportunity to generate “decent work” that is safe, fair, and secure.

Together, these interventions help build stronger partnerships, where private capital, public policy, and grassroots enterprise converge to drive both environmental sustainability and social justice.

Bringing C2C to Life: A Case Study from Goa

Like most urban centres, the small town of Mapusa in Goa dealt with indiscriminate dumping, rising landfill pressures, and poor segregation. Waste from households, markets, and commercial zones often used to ends up mixed and unrecoverable, losing all potential value. Recognising this urgency, 4 and 8-way segregation systems were set up, a bold step to transform the town’s waste ecosystem through the principles of cradle-to-cradle (C2C) circularity.

Waste fractions collected from RWAs, schools, and colleges are sent to the local Dry Waste Collection Centre (DWCC), where they are classified into domestic hazardous and non-hazardous waste. This segregation at source upholds material health by isolating harmful substances early and ensuring recoverable materials remain uncontaminated and safe for reprocessing.

Materials like multilayered packaging, plastics, metals, and textiles are meticulously sorted by trained Safai Mitras (waste workers) and sent to verified recycling partners. These fractions, once considered invaluable, are now re-entering packaging streams, utilities, and upcycled products across different market spaces. Every fraction is treated as a resource, exemplifying material reutilisation without degradation in quality and closing the loop effectively.

These efforts are further strengthened by responsible partnerships with certified recyclers and processors who maintain traceable systems, aligning with the C2C goal of reducing environmental impact in waste recovery. Moreover, the framework supports future transitions toward cleaner and more sustainable energy sources, reinforcing circularity through climate resilience.

Water stewardship, as a key principle, is reflected in the collective responsibility of all stakeholders to manage water resources sustainably. This includes ensuring clean water access, preventing contamination, and safeguarding water quality throughout the water management practices.

Perhaps the most human dimension of Mapusa’s journey is its commitment to social fairness. Safai Mitras, many from historically marginalised communities, are formally recognised as frontline workers. With access to ID cards, financial inclusion, skill-building, and healthcare linkages, these policies restore dignity and security to their lives. Furthermore, the inclusion of women in key sorting and leadership roles has catalysed greater gender equity within Mapusa’s waste ecosystem.

These interventions illustrate how a small town like Mapusa can build a model of “circularity in cities” where waste is not just removed but regenerated. By ensuring no fraction ends up in landfill, Mapusa transforms waste into a valuable resource and circularity into an everyday reality.

This case study is a reflection of the Plastics Lighthouse Project, a CSR initiative by Mondelez India Foods Pvt Ltd and implemented by Anubhuti Welfare Foundation, committed to advancing circularity, environmental stewardship, and social inclusion in India’s urban ecosystems.

Incentivising Waste Segregation Through DWCCs

An integral part of Mapusa’s waste management system is the strategic use of Dry Waste Collection Centres (DWCCs). These decentralised hubs act as both sorting and incentivisation points. Residents and informal workers who bring in well-segregated dry waste are acknowledged through community recognition or small value-based incentives, depending on the recoverable volume.

This micro-incentive system fosters behaviour change, reduces contamination at source, and ensures better-quality recyclables for downstream processing. It also provides livelihood support to micro-entrepreneurs who operate or assist in DWCC management. By creating a visible, rewarding system for segregation, DWCCs enhance community participation while stabilising the economic foundation of circularity.

Looking ahead to creating cleaner and smarter cities

Urban waste circularity represents a profound shift in how cities manage their resources, moving decisively from linear disposal methods toward circular approaches that benefit both the environment and society. This holistic framework integrates environmental integrity with social equity, recognising that sustainability can only be achieved when marginalised communities are empowered and included.

Additionally, achieving circularity in cities also demands collaboration among diverse stakeholders and civil society through innovative partnerships. These stakeholders must act in unison to build waste management systems that are resilient to the growing challenges posed by climate change, urbanisation, and social inequality. Ultimately, this cradle-to-cradle approach is more than a technical endeavour; a pathway to a sustainable, inclusive world where nothing is wasted and everything thrives in harmony.