Abstract

This paper examines the concept of Net Zero Plastic Cities—urban systems designed to reduce plastic use, recover waste, and prevent environmental leakage. Through a global review, it identifies key challenges such as poor waste management, low recycling rates, and implementation gaps in Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR). It also highlights emerging policy tools, infrastructure innovations, and governance models that address these issues. Ahmedabad, India, is presented as a case study using a six-stage assessment framework. Field observations reveal an 88% household segregation rate, increasing integration of the informal sector, and persistent gaps in processing low-value plastics and tracking data. Ahmedabad’s approach—through city-level byelaws, public- private partnerships, and circular reuse practices—offers practical lessons. The paper concludes by outlining scalable strategies that emphasise policy alignment, multi- stakeholder collaboration, and investment in circular infrastructure.

Introduction

Plastic waste is a major global urban sustainability challenge. Plastic production has grown from 2 million tonnes in 1950 to over 450 million tonnes today, generating around 350 million tonnes of waste annually. Mismanaged plastic—neither recycled, incinerated, nor securely landfilled—leads to widespread pollution. Around 0.5% of this waste (1–2 million tonnes) enters oceans each year. A 2024 study estimates over 52 million tonnes of plastic leak into the environment annually, with ~70% from just 20 countries—India, Nigeria, and Indonesia among the top contributors. Poor waste services, affecting 1.2 billion people, lead to open dumping or burning. Consequences include marine pollution, clogged waterways, greenhouse gas emissions, and toxic impacts on ecosystems and human health.

Cities embrace “zero waste” and circular economy models. A related concept is the “Net Zero Plastic City,” inspired by Net Zero Carbon. It aims to eliminate net plastic leakage by cutting waste and offsetting residuals through recycling or recovery. These cities minimise single-use plastics, maximise reuse, and prevent plastic from reaching land, water, or air—creating a closed-loop, sustainable system.

Concept of Net Zero Plastic Cities – Definition and Context

While not formally defined, Net Zero Plastic follows the logic of Net Zero Carbon. As per Plastic Collective, a “Plastic Net Zero” product offsets any environmental plastic leakage through subsequent removal, resulting in no net pollution. At the city level, this principle can be extended as follows:

A Net Zero Plastic City is an urban area that reduces plastic waste generation and offsets any residual leakage by recovering an equivalent amount through recycling, reuse, or other methods—resulting in zero net plastic pollution.

Net Zero Plastic means waste is either prevented at the source or fully recovered, with minimal or no leakage to land or water. It aligns with Zero Waste Cities, which promote circular systems and responsible production, consumption, and recovery. However, Net Zero Plastic specifically targets the unique challenges of plastic pollution.

A Net Zero Plastic City rests on four pillars:

- Reduce – minimise single-use and non-essential plastics;

- Substitute – use biodegradable or reusable alternatives;

- Recover – improve collection, recycling, and safe disposal;

- Offset/Remove – eliminate residual leakage via clean-ups or plastic

These efforts are supported by awareness campaigns, behaviour change, and systems like take-back schemes, deposit-refunds, and refills. Net Zero Plastic retains plastic within a closed-loop economy, balancing its utility with environmental responsibility—making the approach both practical and necessary.

Global Landscape: Challenges and Innovative Approaches towards Net Zero Plastic

Cities globally are adopting measures aligned with net zero plastic goals, even if not formally labelled as such. A review of international experiences reveals shared challenges and innovative approaches. Key insights from this global landscape are outlined below.

- Plastic Waste Generation and Leakage: Urban plastic waste is increasing, with packaging making up over 40% of global use and ~50% being single-use. The US leads with ~42 million metric tonnes annually, followed by India (~26.3 million) and China (~21.6 million). Poor management, especially in lower-income cities, leads to open dumping. Middle-income countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America are major sources of ocean plastic. Expanding infrastructure for collection, sorting, and recycling is essential in rapidly urbanising regions.

- Policy and Regulatory Frameworks: Governments are advancing anti-plastic policies through bans and EPR mandates. Bans on bags, Styrofoam, and straws are now common—from Rwanda’s 2008 ban to EU-wide restrictions. EPR frameworks in the EU, US, and India (2011, updated in 2016 and 2020 with credits and PROs) require producers to fund recycling. While enforcement and infrastructure gaps persist, broader strategies like the EU Plastics Strategy (2018) and India’s Circular Economy roadmap (2021) are steering cities toward waste reduction and circularity.

- Waste Segregation and Recycling Innovations: Source segregation remains limited, with only ~9% of plastic recycled globally; ~50% is landfilled and ~20% mismanaged. Cities use awareness campaigns, multi-bin systems, and incentives to improve rates. Examples include San Francisco’s ~80% diversion, Europe’s colour-coded bins, and Surabaya’s bottle-for-bus-fare scheme. Buy-back centres and waste picker integration aid developing Technologies like optical sorters and chemical recycling offer potential but require investment. Policy support is essential to make recycled plastic competitive with cheaper virgin alternatives.

- Innovative City Initiatives: Several cities are moving toward net zero plastic. Vancouver’s Zero Waste 2040 targets bans and Ljubljana recycles ~68% via door-to-door collection and landfill bans. Seoul’s recycling mandate and waste fees help South Korea reach ~54% plastic recycling. Pune and Bogotá integrate waste pickers into formal systems, boosting recovery and social outcomes. India repurposes low-value plastics—over 33,000 km of roads use recycled plastic— supporting circular economy goals and reducing landfill reliance.

- Stakeholder Collaboration: Achieving net zero plastic requires collaboration beyond city governments. Citizens, businesses, community groups, and higher authorities all have roles. Public-private partnerships boost efficiency, while local engagement—such as Tokyo’s sorting system or women’s groups in Indian towns—enhances impact. Platforms like WWF’s Plastic Smart Cities, C40 Cities, and the Global Alliance for Cities on Plastics support action plans and global knowledge sharing.

Key challenges include rising plastic use, weak infrastructure in the Global South, limited recycling markets, poor enforcement, and entrenched behaviours. Still, cities have tools— bans, EPR, recycling technologies, and inclusive governance. Global momentum is building in 2022, 175 countries committed to a Global Plastics Treaty by 2024. Such frameworks and national circular economy plans can help cities achieve net zero plastic.

Case Study: Ahmedabad’s Journey Toward a Net Zero Plastic City

Ahmedabad, a major Indian city with over 8 million residents, generates over 1,000 metric tonnes of plastic waste monthly. Faced with rapid urbanisation and growing waste, the city has adopted a holistic approach—blending policy, public-private partnerships, and community engagement—to work towards eliminating plastic leakage.

Policy Framework and Local Initiatives in Ahmedabad

India’s Plastic Waste Management Rules (2016, 2018, 2021) mandate segregation, ban select single-use plastics and enforce EPR. Ahmedabad built on this with bye-laws imposing fines for littering and non-segregation. Enforcement targeted bulk waste generators and banned bag distribution. AMC also ran awareness drives like “No Plastic Day” and school programmes promoting reuse and proper disposal.

In 2018, Ahmedabad and UNCRD released a “Roadmap for Zero Waste Ahmedabad” to cut waste at source, expand recycling, and manage residuals. For plastics, it proposed citywide collection, MRFs in all zones, phasing out harmful plastics, and supporting recycling businesses. The roadmap linked waste management to climate goals and features in Ahmedabad’s Climate Action Plan, aligning with India’s Nationally Determined Contribution on urban climate mitigation.

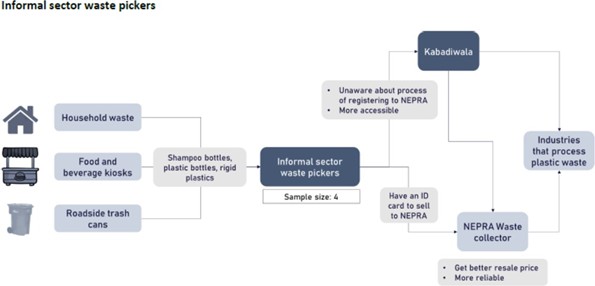

Stakeholders and Governance: Integrating the Informal Sector

A core part of Ahmedabad’s strategy is integrating informal waste pickers. In partnership with NEPRA and the municipal corporation, 1,800 pickers were formalised by 2023 with ID cards, protective gear, and fixed buy-back rates. Incomes rose from ~₹1,500 to

₹6,000/month, boosting collection efficiency and recovery. These efforts help avoid

~200,000 tonnes of CO₂e annually—equal to removing 130,000 cars—by reducing virgin plastic use and open burning. Ahmedabad’s model relies on multi-actor collaboration: the city provides policy and infrastructure, NEPRA brings capital and tech, and informal workers contribute field expertise. Waste pickers are repositioned as environmental service providers, advancing equity and efficiency. Over 90% of households receive doorstep collection by municipal teams, while authorised recyclers handle sorting. NGOs and resident groups support outreach. AMC holds regular stakeholder meetings to address system gaps and ensure coordinated action.

Infrastructure and Implementation: From Segregation to Recycling

Ahmedabad has made major infrastructure gains in waste segregation and recycling. By 2023, ~88% of households were segregating waste—up from near zero in a decade— matching top cities under Swachh Bharat. This aligns with India’s national urban average of ~88%. The city uses partitioned vehicles for wet and dry waste and operates eight transfer stations and MRFs. Through public-private partnerships, NEPRA’s “Let’s Recycle” facility processes ~500 tonnes of dry waste daily. PET is recycled into fibres, while low-value plastics are reused in benches, bins, roads, or co-processed in cement kilns—diverting residual waste from landfills.

Despite 88% segregation, quality issues persist due to contamination. AMC enforces fines and allows waste rejection for non-compliance. Markets for low-grade plastics remain weak, requiring subsidies or niche uses. Ahmedabad is accessing EPR funds via Producer Responsibility Organisations and is developing an IT system to track plastic flows and support plastic credit accounting. Its strategy includes plastic reduction through bans or taxes, improved segregation with coloured bins, expanded recycling via new technologies, and reuse in roads and plastic lumber. Roles are clearly defined, and a phased action plan is under implementation.

On-the-ground experience coupled with insights.

Ahmedabad’s plastic governance reflects local realities. With many families dependent on waste picking, the city prioritised “integration over elimination”—partnering with cooperatives and NEPRA to formalise livelihoods while improving waste outcomes. The strategy follows phased, context-specific targets, starting with bans on bags and

Styrofoam, then addressing complex materials like multilayer packaging. Data and monitoring underpin progress, using metrics like segregation and recycling rates. Pilot wards with active resident associations saw near 100% segregation, prompting broader community leadership. Targeted clean-up drives in busy markets helped build public confidence through visible results.

In summary, Ahmedabad’s journey illustrates how a city can translate the lofty idea of Net Zero Plastic into concrete practice: through strong local policies, inclusive stakeholder engagement, improved infrastructure, and continuous learning and adaptation. While not net zero yet, Ahmedabad has significantly improved its plastic waste outcomes and set itself on a trajectory toward that goal.

Toward Scalable and Replicable Models

The lessons from Ahmedabad and other pioneering cities feed into a broader question: how can the Net Zero Plastic City model be scaled up across India and globally? The concluding insights point to several scalable and replicable strategies:

- Robust Policy Backing with Local Adaptation: A supportive policy environment is National frameworks like India’s PWM Rules and the upcoming Global Plastics Treaty offer direction, but cities must adapt solutions locally. Ahmedabad’s mix of regulation and incentives—penalties for non-segregation alongside support—offers a replicable model. Strengthening EPR systems is also key, enabling cities to access producer-funded support for recycling infrastructure—a globally relevant financing approach.

- Integrated Waste Management Planning: Cities should adopt structured planning, like Ahmedabad’s six-stage framework, covering waste diagnostics, stakeholder engagement, baseline setting, and phased strategies with Such models are transferable—any city can start with assessing its plastic waste situation. Toolkits like the Plastic Smart Cities Guide offer templates for baseline assessments and action plan development to support this process.

- Stakeholder Empowerment and Inclusion: Success depends on engaging all stakeholders. Ahmedabad’s model of integrating informal waste workers through cooperatives is replicable in other Indian and low-income cities, offering both environmental and socio-economic gains. Citizen engagement is equally vital— campaigns like Indore’s “plastic jyadti se azadi” show how locally tailored messaging can mobilise communities. The core principle is building shared responsibility for addressing plastic waste.

- Technology Transfer and Innovation Scaling: Technical innovations can be scaled across India’s plastic-asphalt roads offer a replicable model for cities with plastic surplus and road needs. Low-tech options like “eco-bricks” are spreading in Asia and Africa. City networks should facilitate innovation exchange. International donors and climate finance can aid tech transfer—such as sorting automation, pyrolysis for plastic-to-oil conversion, and digital tracking—helping more cities move towards net zero plastic.

- Monitoring and Accountability: Scalable models need robust monitoring, reporting, and verification. Like climate reporting, cities should track plastic metrics—collection, leakage, and recycling rates. Common indicators, potentially under the upcoming global treaty, can enable benchmarking and peer learning. India’s Swachh Survekshan rankings show how friendly competition can drive progress. Transparency is key—publishing data and involving communities in audits (e.g., local litter checks) helps build accountability and sustained

Conclusion

Pursuing Net Zero Plastic Cities is a critical step toward sustainable, circular economies. Global policy shifts and pilots show growing momentum, while Ahmedabad offers a replicable model of localised action in a developing context. Its combination of expert guidance and ground-level innovation serves as a practical blueprint. As more cities adopt such approaches, plastic waste can shift from being a threat to a managed resource. Reaching net zero plastic is a continuous journey—but one that cities worldwide are now undertaking for a cleaner, circular urban future.

References

1. Plastic Collective. (2022). What Does Plastic Net Zero Mean? – Definition of

“Plastic Net Zero” product and concept of net zero plastic pollution.

2. Choudhary, A. (2023). Towards Net-Zero Plastic Cities: An Integrated Framework for Plastic Waste Management in Ahmedabad City. Master’s Thesis, CEPT University. – Provides concept of Net Zero Plastic City, six-stage framework, and case details for Ahmedabad.

3. Ritchie, H. et al. (2022). Plastic Pollution – Our World in Dataourworldindata.orgourworldindata.org. – Global plastic production and waste statistics, mismanagement and recycling rates, data visualization of waste flows (Figure 1).

4. Ashworth, J. (2024). Almost 70% of all plastic waste is produced by just 20 countries. Natural History Museum Newsnhm.ac.uknhm.ac.uk. – Study findings on plastic pollution hotspots, India’s contribution, and global treaty context.

5. World Economic Forum. (2023). How India is creating collaborative solutions to tackle waste weforum.orgweforum.org. – Indian plastic waste generation (9.4 MT/year, ~50% processed) and Swachh Bharat Mission achievements (94% collection, 88% segregation).

6. ICLEI USA. (2023). State and Local Governments Collaborate to Reduce Plastic Pollution icleiusa.orgicleiusa.org. – Describes EPR programs in U.S. states and their importance for local governments (example of Oregon’s Packaging Act).

7. TERI. (2021). Circular Economy for Plastics in India: A Roadmap teriin.orgteriin.org. – Discusses India’s EPR policy evolution, implementation challenges (awareness, infrastructure, informal sector integration) and recommendations.

8. Oates, L. et al. (2018). Reduced waste and improved livelihoods for all: Lessons from Ahmedabad, India. Coalition for Urban Transitions newclimateeconomy.netnewclimateeconomy.net. – Case study on integrating waste pickers in Ahmedabad, improved recycling rates, quadrupled incomes and CO2 reductions (~200,000 tonnes/year).

9. Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation & UNCRD. (n.d.). Road Map for Zero Waste Ahmedabad. – City-level strategic plan outlining approaches for waste reduction, including plastic waste interventions.

10. Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation. (n.d.). Plastic Waste Management Bye-Laws.

– Local regulation imposing source segregation and anti-littering fines in Ahmedabad.

11. Plastic Smart Cities – WWF. (2021). City Action Plan Guide plasticsmartcities.orgplasticsmartcities.org. – Framework for cities to develop action plans on plastic waste (baseline assessment, stakeholder consultations, etc.), used as reference for best practices.