The Global Plastics Treaty, initiated by Rwanda and Peru at the Fifth Session of the UN Environment Assembly (UNEA) in Nairobi in 2022, aims to address plastic pollution through a legally binding international agreement covering the entire lifecycle of plastics.

The UNEA resolution, supported by over 175 countries, mandated formal negotiations under the United Nations Environment Programme to develop and adopt this treaty by the end of 2024. In 2022, an ad hoc Open-Ended Working Group was established to prepare for the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC), which began its work that same year. The INC, responsible for conducting the treaty negotiations, has held five sessions.

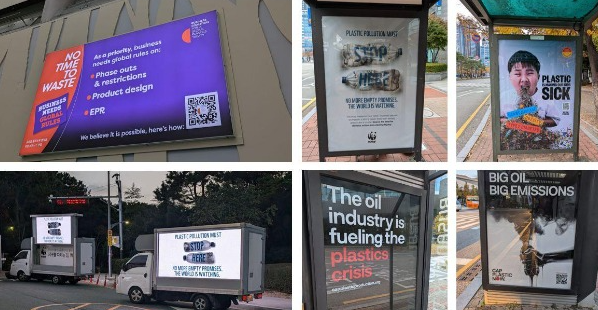

The most recent session concluded in Busan, South Korea, last December. This fifth INC failed to reach an agreement on adopting a plastic pollution treaty. Key disagreements centred on goals and measures for reducing overall plastic production and on addressing the use of harmful chemicals in plastic products. The INC was adjourned and will resume negotiations in the second half of 2025.

Beyond borders – strategies and coalitions in the global plastic treaty negotiations

During the two-and-a-half years of negotiations, two distinct strategies emerged.

Firstly, the so-called ‘like-minded countries’ – primarily oil and/or plastic-producing nations – employed a tactic of delay and derailment. Facing mounting pressure and the weight of public opinion, they resorted to abusing the consensus rule, obstructing intersessional work between INC meetings, and boycotting substantive discussions until the eleventh hour. Their aim was to prolong the negotiations, forcing a majority of countries to accept a low-ambition treaty.

Secondly, the High Ambition Coalition to End Plastic Pollution, comprising 68 countries, developed a counter-strategy in response to the persistent obstructionism of the low-ambition bloc. This strategy emerged from a growing sense of collective empowerment and a shared understanding of the need for ambitious action. Drawing lessons from the failures of other recent multilateral negotiations, the High Ambition Coalition steadfastly maintained its position on the level of ambition, preventing the process from concluding with a weak agreement

Was Busan a turning point for the plastic treaty negotiations ?

The outcome of this fifth session can be seen both as a success and as a failure.

A failure because negotiators exhausted the allocated time and, whilst plastic pollution continues to increase, no agreement was found. A success because the process, as extremely slow and painful as it was, has delivered a text; and, more importantly, has raised enough awareness among the negotiators to draw a line of ambition and stand behind it.

The agreement stalled due to several key sticking points. Disagreement arose over which plastic products and chemicals of concern should be banned or phased out, requirements for product design, and the scope of financing mechanisms.

A major point of contention was the inclusion of supply-side measures and production targets. The “High Ambition Coalition” of countries advocated for a legally binding cap on plastic production, citing the need to curb plastic pollution and the urgent need for action. However, this proposal encountered significant resistance from major oil-producing nations. These countries maintained unwavering stances on any potential production targets, advocating instead for a focus on waste management strategies, such as enhanced extended producer responsibility

The “High Ambition Coalition” pushed for stronger measures to identify and regulate chemicals of concern used in plastics, while some countries resisted these measures, citing existing international agreements and national regulations. Environmental organisations and scientists emphasised the need for evidence-based decision-making to address this critical issue.

Some disagreement remain as well on funding sources and allocation mechanisms for a dedicated multilateral fund to support developing countries in meeting their obligations under the treaty, or for using existing environmental funds, such as the Global Environment Facility.

A fresh political wind to drive upstream action and an ambitious, legally binding instrument against plastic pollution

A glimmer of hope emerged at the conclusion of the negotiations. Indeed, a coalition of more than one hundred ambitious nations, led by the High Ambition Coalition under strong leadership from Norway, Rwanda, the European Union, the United Kingdom, and Small Island Developing States, refused to settle for a watered-down, lowest-common-denominator agreement based on voluntary measures. They have publicly committed to a global target to cut plastic production, global phase-outs of toxic chemicals and plastic products, a fair deal on finance for the most affected parties, and ensuring the option to vote is maintained for future amendments. Therefore, they held the line, rejecting a weak treaty that would have done little to address this systemic problem

This resolute stance signifies the rise of a progressive, rule-making majority, signifying a crucial turning point in the treaty negotiation process. Never before have so many countries aligned on the importance of upstream actions.

As aptly summarised by Juan Carlos Monterrey Gómez from the Panaman delegation, the “momentum is with this overwhelming majority” highlighting their newfound collective agency and their capacity to influence the trajectory of the negotiations.

In parallel, the Business Coalition for a Global Plastic Treaty – composed of over 260 members – sent a powerful message: enforceable global rules are essential.

Moving forward, negotiations should capitalise on this progress to develop a robust treaty that addresses the full lifecycle of plastics.

Beyond Busan: what do the next steps look like for the plastic treaty negotiations?

Looking ahead, negotiations are expected to resume in 2025 for at least one further round. However, the current negotiating method has clearly reached its limits. If both factions in the negotiations remain entrenched in their positions, no treaty will be possible, regardless of the number of INCs convened.

To capitalize on the momentum generated in Busan, the progressive majority must utilize the time leading up to the resumed negotiations effectively. This could involve increased ministerial participation. During the closing plenary of INC-5, Canada and the EU called for ministers to be invited to the next session. While civil servants are well-trained in representing their countries’ positions, they often lack the flexibility to move beyond pre-determined positions and engage in meaningful compromise, unlike ministers.

Alternatively, the negotiation format itself could be revised. A plastic pollution treaty could be agreed upon within the existing UNEA process, or, if deemed necessary, states could conclude the treaty outside of this framework. One potential path involves those states committed to an ambitious plastics pollution treaty convening a separate plenipotentiary conference. This conference would establish its own rules of procedure and adopt an ambitious treaty text through a tailored diplomatic process that prioritizes ambition and urgency. These countries could then sign and ratify the treaty, bringing it into force. The treaty could subsequently be open to accession by all states. Furthermore, the treaty could include provisions for engaging with non-parties. Several treaties have been negotiated and adopted outside of the UN and other intergovernmental fora. Notable examples include the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), and the Ottawa Convention on Land Mines.

Another option within the UNEA process involves focusing on areas of consensus while deferring contentious issues for future discussions. This approach could involve deferring discussions on primary plastics production and chemicals of concern in products. The treaty would prioritize agreed-upon measures, such as product design standards, resource efficiency, waste management, and a circular economy approach. This would enable countries to collaborate on immediate, impactful solutions while building trust and momentum for future negotiations.

Under this scenario, high-ambition countries could lead by implementing stricter domestic measures (permitted under the treaty), investing in innovation, and providing financial and technical support for global implementation.

Regardless of the chosen approach, measures for transparency and accountability will be crucial. These include a global plastics monitoring system to track product chemistry, production, trade, and consumption, as well as encouraging national strategies to align production and consumption with sustainability goals.

While this “less ambitious” approach may not be ideal, it could still achieve significant progress by addressing immediate priorities, respecting diverse perspectives, and laying the groundwork for a comprehensive solution in the future.

The urgency of the plastic pollution crisis demands decisive action; the time for a robust, binding treaty that addresses the entire lifecycle of plastics is now. Therefore, before INC-5.2, states seeking solutions should carefully consider the various options available to them to advance towards their desired outcome. Whatever approach is adopted, another impasse must be avoided.

Circular Economy Policy Advisor