Abstract

Climate change is adversely impacting the water resources, often accentuating the water stress in countries with competing water demand from various sectors. Reusing treated domestic used water for non-potable purposes offers potential to reduce the pressure on freshwater resources and build community resilience to changing climate. This article presents an indicator-based framework for assessing the performance of Indian urban local bodies (ULBs) in managing their municipal used water. The framework is built using 25 parameters across five key themes that includes finance, infrastructure, efficiency, data and information and governance. A case study on application of the developed framework to the City of Thane in western India is discussed as a test case. The framework has a potential to guide ULBs in formulating strategies to strengthen used water treatment and reuse, thus integrating a circular economy approach to water management.

Key words: India; Climate Change; Domestic Used Water; Circular economy; Urban local bodies; Finance; Data and Information

1. Introduction

Climate change is fundamentally altering Earth’s hydrological cycle, creating unprecedented challenges for water resource management worldwide. Extreme precipitation events have increased by about 7% for every 1-degree Celsius rise in temperature (IPCC 2007). The situation is alarming in the Global South, particularly India. Climate change-induced monsoon variability has triggered contrasting wet and dry conditions, leading to increased incidents of hydro-meteorological disasters in India (TMC and CEEW 2024, Mohanty and Wadhawan 2021). As per an analysis of climatic disasters between 1971 and 2020, around 75% of India’s districts are prone to severe hydro-meteorological disasters, of which nearly 40% show a swapping pattern (Prabhu and Chitale 2024), alternating between drought and floods, leading to compounding risk.

In India, 22% of water basins are experiencing rapid changes in the area covered by surface water (UN Water 2020a). Further, about 70% of the country’s water supply is contaminated (NITI Aayog 2019). This complexity calls for adaptation efforts such as improving water use efficiency and exploring unconventional sources of water such as the reuse of treated used water (TUW). The latter is a shift from a linear to a circular economy approach that views used water as a resource, rather than a source of pollution.

Globally, approximately 380 billion cubic metres (BCM) of municipal used water is generated annually, with Asia accounting for the largest share (42%). Among the South Asian countries, India has the highest municipal (domestic) used water generation of 26.41 BCM annually (Niti Aayog 2022, CPCB 2021). This substantial amount of used water, if treated (to the desired quality standard) and reused, offers tremendous potential in ensuring water security and building climate-resilient cities. The TUW available in India (in 2021) for the irrigation sector, identified as one of reuse avenues, was sufficient to irrigate about 1.38 million hectares (Mha) of land, increasing to over 3 Mha by 2050 (Bassi, Gupta, and Chaturvedi 2023). Further, this could have: a) reduced fertilizer requirement by 9-10% due to its inherent nutrient value (Bassi, Gupta, and Chaturvedi 2023); and b) decreased groundwater pumping in 3.5% of the groundwater-irrigated area in 2021. Both these aspects further could have reduced GHG emissions by 1.3 million tonnes in 2021 and 2.2 million tonnes by 2050 (Bassi, Gupta, and Chaturvedi 2023) under the business-as-usual scenario. Thus, mainstreaming circularity in used water management can effectively contribute towards building climate resilience of water infrastructure by reducing the dependence on freshwater resources, mitigating groundwater depletion and reducing GHG emissions by minimising energy intensive groundwater pumping.

Despite such immense potential, TUW reuse is yet to be integrated in water resources planning by India cities. Of the total municipal domestic used water generated in India, less than a third is treated (CPCB 2021), against the global average of 58% (UN-Water 2020a). Further, only 26.7% of households are connected to an underground drainage network (Jain et al. 2024). The inability to scale up collection and treatment infrastructure and meet prescribed effluent water quality standards further lowers the potential for TUW reuse. The situation is similar in many other countries of the Global South, Chad, Colombia and Papua New Guinea (UN-Water 2020a).

In terms of municipal used water governance, only 12 Indian states have a dedicated policy (in various stages of development) on the safe reuse of TUW (NMCG 2022). It is important to note that while state policies play a facilitating role, the impetus for implementing used water treatment and reuse lies in the action plans, guidelines, and projects realised at the ULB level (Gupta et al. 2024). Therefore, city-level TUW reuse planning is essential to guide sustainable used water management in the long-term. But the lack of a standardised assessment of the current municipal used water management scenario deters transparency, accountability, and informed decision-making for mainstreaming TUW reuse.

With this background, a Municipal Used Water Management (MUWM) index framework was developed for assessing the performance of Indian ULBs in used water management. The developed index was piloted in Thane City in western India to demonstrate its potential in guiding ULBs to identify the areas that require improvement and, hence, investment for improving used water management.

Following the introduction, the second section of the article provides a review of the existing indicator frameworks to assess ULBs performance. The third section introduces various parameters and themes considered for developing the indicator framework. The fourth section provides the computation of the index value based on the developed framework. The fifth section presents the test case and the last section is the conclusion.

2. Review of selected existing performance indicator frameworks

Overall, ten existing Indian and global performance indicator frameworks related to urban water management across municipal, state and national level assessments were analysed. They include the City Water Resilience Framework, Composite Water Management Index, Climate Smart Cities Assessment Framework, Municipal Performance Index, OECD Water Governance indicators, Service Level Benchmarking, State Energy Efficiency Index, Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), Swachh Survekshan Toolkit, and Water Sensitive Cities Index (UN 2024, Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs 2023, 2022, 2020, Ministry of Power 2023, Rogers et al. 2020, Niti Aayog 2019, OECD 2018, Shouler and Ruiz-Apilanez 2018, MoUD 2008). The review focused on their scope of application, thematic areas evaluated, and relevance to used water management. Based on this, the prevalent gaps in existing frameworks were identified.

Over the years, efforts have been made by international organisations and national agencies to collectively assess the performance of states and cities in different aspects of service delivery in urban areas. The progress in developing indicator-based performance assessments is a heterogeneous landscape, due to the difference in approach, application and goals (Berger et al. 2022). For instance, some frameworks are aimed at boosting performance through benchmarking such as the Water Sensitive Cities framework (Chatterfield et al. 2016), while some are meant to catalyse stakeholder dialogue for better water governance (OECD 2018). However, international frameworks often do not represent the Global South well due to the difference in development priorities, data, planning, and implementation of water resource management (Starkl et al. 2022, Kumar et al. 2021).

Nationally, the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs (MoHUA) has initiated multiple municipal ranking exercises that evaluate a city’s performance across sectors (MoHUA 2020, 2022, 2023). The most measured indicators in used water management are often the absolute used water generation and the infrastructural capacity to treat used water (MoHUA 2020, 2022, 2023, NITI Aayog 2019). Some national frameworks have evaluated circularity in used water management by measuring the extent of treated used water reuse in the city (MoHUA 2022, 2023, NITI Aayog 2019, MoUD 2008). While frameworks such as the Swachh Survekshan tool, the Municipal Performance Index, and the Climate Smart Cities Index exist that evaluate used water management through varying lenses of performance evaluation, there is a dearth of a focused framework that holistically assesses the management scenario of used water as a resource. Further, the assessment of integral components such as operational efficiency, financial security, access to data and information, and governance structure is not well represented in existing frameworks. The knowledge of these components is necessary to identify the weaknesses within the used water management cycle and improve the working of various elements involved in its functioning. The study builds on the existing frameworks and indices to address the highlighted gaps, and develop a targeted framework enabling the mainstreaming of a circular economy approach to used water management at the ULB level in India.

3. Development of the municipal used water management assessment framework

The Municipal Used Water Management (MUWM) assessment framework is inspired by the UN Global Accelerator framework that aims to catalyse action towards achieving targets under the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 6 on universal access to clean water and sanitation through five accelerators – financing, data and information, capacity development, innovation, and governance (UN Water 2020b). In doing so, the framework addresses the multiple challenges that impede the mainstreaming of circular economy in used water management.

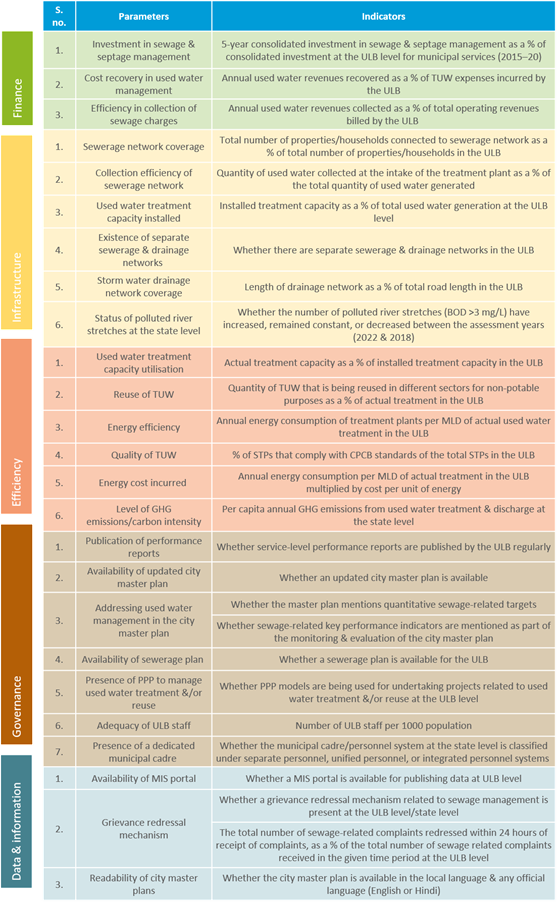

Based on this, the MUWM assessment framework has been developed as a targeted framework that evaluates a ULB across five themes that are crucial for comprehensive used water management in cities. The framework follows a theme – parameter – indicator approach, where each theme is composed of multiple parameters, and each parameter is measured by one or more qualitative or quantitative indicators used to assign a score to the ULB. The selection of parameters and corresponding indicators is based on their ability to capture maximum information on the used water management scenario. The five selected themes along with their corresponding parameters and indicators are presented in Figure 1. The estimation method for each indicator and relation to index score can be referred in Gupta et al. 2024. Every indicator relates to the index score either directly or inversely; a direct relationship signifies that a higher the indicator score, higher will be the composite index value, whereas an inverse relationship will lead to a decrease in the final composite index value.

Overall 25 parameters and 27 indicators were identified across 5 themes. Most of the indicators were specific to the ULBs. However, some were state-level indicators whose values can be considered as proxy for all the ULBs in the respective state. These indicators include: the status of polluted river stretches, per capita annual GHG emission from used water treatment and discharge, and the classification of municipal cadre/ personnel system.

The developed framework was finalised after a stakeholder consultation with 11 representatives from government agencies (such as ULBs) and non-government experts and practitioners, representing think tanks and academia. The feedback from the consultation process was incorporated to increase the framework’s robustness.

4. Computation of index scores

The official reports published by the national and state level government agencies are the primary source of data for computing values of various indicators considered for developing the MUWM framework. Out of the others, Service Level Benchmarking (SLB) reports published by state governments provided valuable data and information on the status of the used water management for most of the selected ULBs. Also, self-reported data from ULB websites provides information on city-level actions and initiatives on used water management. For the computation of the composite index score, the estimated value for each indicator needs to be normalised, weighted and aggregated for each ULB. These steps are explained below.

4.1. Normalisation

The maxima and minima normalisation technique need to be applied to convert the raw quantitative indicator data into a dimensionless score of 0-1 for comparative analysis. This method assigns 0 to the minimum value of the dataset and 1 to the maximum value (Highland and Zhou 2022). In case of a direct relationship between indicator and index, equation 1 should be used for normalisation:

(1)

Where x is the value of a specific indicator for a ULB

Alternatively, in a scenario where an indicator has an inverse relationship with the index, a modified equation can be used for normalisation:

(2)

In cases where each parameter has more than one indicator, the arithmetic mean of the indicator scores needs to be calculated to arrive at a single parameter score. Qualitative data should be converted to either a binary value of 0 or 1, or a value on an ordinal scale between 0 and 1, with classes for each such indicator (table 1).

4.2. Weightage

For the assessment of ULBs spanning multiple states and varying geographies, each parameter across all themes can be assigned equal weightages due to their equal importance in assessing municipal performance in used water management. Aggregated theme scores, hence depend on the number of parameters within each theme.

4.3. Aggregation

First, the normalised scores should be aggregated for each theme by adding the individual parameter scores. Next, the composite index score needs to be computed by further aggregated the individual theme scores and multiplying the sum by a weighted factor of 5/25 with numerator represented 5 themes with parameters having equal weightage and denominator representing the 25 indicators. The final composite index score for each ULB lies within the 0-5 scale. The computation methodology is summarised in Table 1.

Table 1: Methodology of MUWM index computation

Sr. no. | Theme | No. of parameters | Aggregated normalised theme score | Range for normalised theme score | Weighted factor | Composite index score (0 – 5) |

1. | Finance | 3 | A | 0–3 | 5/25 | 5/25 (A+B+C+D+E)

|

2. | Infrastructure | 6 | B | 0–6 | ||

3. | Efficiency | 6 | C | 0–6 | ||

4. | Governance | 7 | D | 0–7 | ||

5. | Data and Information | 3 | E | 0–3 | ||

Overall | 25 | |||||

Source: Authors’ analysis

4.4. Categorisation of Urban Local Bodies

Depending on the composite index score, the ULBs can be classified into five award categories, i.e. outstanding, leading, performing, promising and aspiring. The ‘0’ meant the lowest category (aspiring) and ‘5’ meant the highest category (outstanding). The categories are substantiated in Table 2.

Table 2: Award categories under the MUWM index

Category | Composite Index score range (0–5) | Description |

Outstanding | 3 and above | Such ULBs have achieved the highest scores on the MUWM index. Their comprehensive approach to used water management can serve as an example for others to follow and take inspiration from. |

Leading | 2.25–3 | These ULBs are front runners in terms of performance in used water management. They have achieved substantial success in most of the thematic areas, and even regarding the remaining aspects, their on-ground efforts have the potential to make an impact at scale in the near future. |

Performing | 1.5–2.25 | These ULBs have made notable strides in used water management. They have made substantial progress on at least one or two themes, with efforts being undertaken across different parameters. |

Promising | 0.75–1.5 | These ULBs are in the transition phase between aspiring and performing. They are yet to make any substantial progress on any of the themes, but have undertaken a number of interventions for used water management under different parameters. |

Aspiring | 0–0.75 | Aspiring ULBs are in the initial stages of improving their used water management. They are exploring and laying the groundwork across different themes, but have yet to undertake any significant interventions. |

Source: Authors’ analysis

4.5. Assumptions

The indicator-based framework was developed on certain assumptions. It assumed that publicly available data sources provide comprehensive and up-to-date information. For the Infrastructure theme, indicators focused on centralised sewage networks due to inconsistent documentation of decentralised and on-site sanitation systems. Energy consumption estimates for used water treatment excluded pumping costs. The financial indicator for investments in sewage and septage management was limited to AMRUT cities as they only publish such data sets in State Annual Action Plans. Lastly, staffing adequacy assessments need to be based solely on staff numbers due to the lack of data on skill levels.

5. Testing of the framework in Thane Municipal Corporation

Thane, a satellite city of Mumbai in the western Indian state of Maharashtra, has a population exceeding 2.5 million and spans an area of approximately 128 square kilometres. The Thane Municipal Corporation (TMC) has recently launched a pioneering TUW reuse plan, utilising the MUWM assessment framework to evaluate the city’s used water management systems.

TMC is categorised as a Leading ULB on the MUWM index, achieving a composite index score of 2.83 out of 5 (Table 3). The ULB demonstrates strong performance in the Finance theme, excelling across all three parameters: investment in sewage and septage management, cost recovery in used water management, and efficiency in sewage charge collection. It also performs well under the Infrastructure theme, with an installed treatment capacity that exceeds the volume of used water generated. However, due to limitations in operational efficiency, only 73% of the total used water generated is currently being treated. Of this, merely 5% is reused, highlighting significant potential for improvement in water reuse practices. To enhance used water treatment and reuse, there is a pressing need to mobilise financial resources for both structural and non-structural infrastructure upgrades.

TMC’s weakest performance is in the Data and Information theme, where it scores only 0.71 out of 3. The absence of a dedicated Management Information System (MIS) portal hampers its ability to report and track performance data related to urban services like sewage management. Establishing a robust data management and sharing system aligned with the MUWM framework would help build a baseline database for municipal used water management. This is crucial for raising awareness about TUW as a valuable resource and informing policy decisions related to reuse.

Table 3: The composite index score and theme scores of Thane city using the MUWM framework

Theme | Scores | Maximum | Category |

Finance | 2.83 | 3.00 | Outstanding |

Infrastructure | 4.22 | 6.00 | Leading |

Efficiency | 3.29 | 6.00 | Performing |

Governance | 3.04 | 7.00 | Performing |

Data and information | 0.71 | 3.00 | Promising |

Composite index score | 2.83 | 5.00 | Leading |

Source: TMC and CEEW 2025

6. Conclusion

The article provides a first-of-its-kind urban MUWM index for assessing the performance of used water management at the ULB or local government level. As demonstrated by the Thane city test case, the computed index value can provide a useful tool to ULBs who are the primary authorities responsible for developing and maintaining used water infrastructure and service delivery in Indian cities, to measure their performance over a temporal scale.

The index generates a baseline information and provides guidance to ULBs who are looking to formulate and adopt long-term plans to integrate circularity in used water management. Such planning should define clear treatment and reuse targets for used water, factoring in the current and future water demand, as well as planned urban development. Additionally, it should include financially sustainable business models and funding mechanisms for implementing reuse projects (TMC and CEEW 2025).

Finally, access to updated and reliable data and information is essential to develop new policies and plans and update existing ones. The assessment framework developed can serve as a template for maintaining and updating municipal data on used water management. The index can hence be developed annually, based on a dynamic data inventory regularly updated with ULBs’ support. Such timely assessments can promote cross-learning and healthy competition among cities.

References

- Bassi, Nitin, Saiba Gupta, and Kartikey Chaturvedi. 2023. “Reuse of Treated Wastewater in India Market Potential and Recommendations for Strengthening Governance.” New Delhi: Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW).

- Berger, Lena, Adam Douglas Henry, and Gary Pivo. 2022. “Orienteering the Landscape of Urban Water Sustainability Indicators.” Environmental and Sustainability Indicators, December, 100207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indic.2022.100207.

- Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB). 2021. National Inventory of Sewage Treatment Plants in India. New Delhi: Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, Government of India.

- Highland, Daniel, and Gang Zhou. 2022. “A Review of Detection Techniques for Depression and Bipolar Disorder.” Smart Health 24 (April): 100282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smhl.2022.100282.

- IPCC. 2007. “FAQ 3.2 – AR4 WGI Chapter 3: Observations: Surface and Atmospheric Climate Change.” Archive.ipcc.ch. 2007. https://archive.ipcc.ch/publications_and_data/ar4/wg1/en/faq-3-2.html.

- Jain, Anoop, Caleb Harrison, Akhil Kumar, Rockli Kim, and S. V. Subramanian. 2024. “Examining Geographic Variation in the Prevalence of Household Drainage Types across India in 2019-2021.” Npj Clean Water 7 (1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41545-024-00355-0.

- Kumar, Sameer, Siddh Doshi, Gargi Mishra, and Mona Iyer. 2021. “Making Indian Cities Water-Sensitive: A Critical Review of Frameworks.” Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering, November, 277–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-5501-2_23.

- Mohanty, Abinash, and Shreya Wadhawan. 2021. “Mapping India’s Climate Vulnerability a District-Level Assessment.” New Delhi: Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW).

- MoHUA . 2023. “Swachh Survekshan Toolkit.” MoHUA, Government of India.

- —. 2022. “ClimateSmart Cities Assessment Framework 3.0 Technical Document.” New Delhi: Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs, Government of India. https://niua.in/c-cube/sites/all/themes/zap/assets/pdf/CSCAF_3_0_Technical_document.pdf.

- —. 2020. “Municipal Performance Index 2020.” New Delhi: MoHUA, Government of India. https://smartcities.gov.in/sites/default/files/2023-07/MoHUA%20Municipal%20Performance%20Index%20MPI%202020.pdf.

- Ministry of Power. 2023. “State Energy Efficiency Index 2023.” New Delhi: Ministry of Power, Government of India. https://stateenergyefficiencyindex.in/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/seei-2023-report.pdf.

- Ministry of Urban Development (MoUD). 2008. “Handbook of Service Level Benchmarking .” New Delhi: Central Public Health and Environmental Engineering Organisation.

- Niti Aayog. 2022 – NITI Aayog 2022. “URBAN WASTEWATER SCENARIO in INDIA.” New Delhi: Atal Innovation Mission (AIM), NITI Aayog. https://www.niti.gov.in/sites/default/files/2022-09/Waste-Water-A4_20092022.pdf.

- – . 2021. “Best Practices Compendium: Urban Transformation Sector.” New Delhi: Development Monitoring and Evaluation Office (DMEO), NITI Aayog.

- –. 2019. “Composite Water Management Index.” New Delhi: Niti Aayog. https://www.niti.gov.in/sites/default/files/2023-03/CompositeWaterManagementIndex.pdf.

- NMCG. 2022. “National Framework on Safe Reuse of Treated Water .” New Delhi: National Mission of Clean Ganga (NMCG), Ministry of Jal Shakti (MoJS).

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. 2018. OECD Water Governance Indicator Framework. OECD Studies on Water. OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264292659-en.

- Prabhu, Shravan, and Vishwas Chitale. 2024. “Decoding India’s Changing Monsoon Patterns a Tehsil-Level Assessment.” New Delhi: Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW).

- Rogers, B.C., G. Dunn, K. Hammer, W. Novalia, F.J. de Haan, L. Brown, R.R. Brown, et al. 2020. “Water Sensitive Cities Index: A Diagnostic Tool to Assess Water Sensitivity and Guide Management Actions.” Water Research 186 (November): 116411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2020.116411.

- Shouler, Martin, and Inigo Ruiz-Apilanez. 2018. “City Water Resilience Framework.” Arup. https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/City%20Water%20Resilience%20Framework.pdf.

- Starkl, Markus, Norbert Brunner, Sukanya Das, and Anju Singh. 2022. “Sustainability Assessment for Wastewater Treatment Systems in Developing Countries.” Water 14 (2): 241. https://doi.org/10.3390/w14020241.

- TMC, and CEEW. 2025. “Treated Used Water Reuse Plan for Thane City.” New Delhi: Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW). https://www.ceew.in/sites/default/files/tmc-reuse-plan-web-version.pdf

- – . 2024. “Thane City Action Plan for Flood Risk Management 2024.” New Delhi: Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW).

- UN Water. 2020a. “Indicator | SDG 6 Data.” Sdg6data.org. United Nations (UN). 2020. https://sdg6data.org/en/indicator/6.3.1.

- – .2020b. “The Sustainable Development Goal 6 Global Acceleration Framework.” United Nations. https://unsceb.org/sites/default/files/2021-06/Global-Acceleration-Framework.pdf.

- United Nations. 2024. “Global Indicator Framework for the Sustainable Development Goals and Targets of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.” https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/indicators/Global-Indicator-Framework-after-2024-refinement-English.pdf.