In recent years, the concept of a circular economy has gained significant prominence across global policy frameworks, sustainability agendas, and urban waste management strategies. In India, this discourse was notably catalyzed with the launch of NITI Aayog’s Circular Economy initiative in 2021, giving a much-needed policy and institutional momentum to the sector. The essence of circularity, centered on the principles of reduce, reuse, and recycle, is not new to India. These values have been deeply embedded in Indian traditions, where frugality, resourcefulness, and the avoidance of waste were part of daily life. However, with rapid urbanisation, rising economic prosperity, changing consumption patterns, and limited source segregation of waste, managing waste at the city scale has become increasingly complex.

What has fundamentally changed is the way the circular economy philosophy is operationalized today. Cities are no longer looking at waste management merely through the lens of visual cleanliness or basic public health outcomes. Instead, they are moving toward structured and scalable models that focus on resource recovery, value creation, market linkages, and environmental resilience. The circular economy today is being built on a foundation that integrates technology, policy, behavior change, and private sector participation. This transition reflects not just a shift in terminology but a complete reimagining of how materials are valued, handled, and reintegrated into the economy through systems that are viable, replicable, and rooted in practical logic.

The 3R framework—reduce, reuse, recycle—has long been accepted as a guiding principle for sustainable waste management. Yet, in most practical conversations and interventions, it is the last R, Recycling, that often receives disproportionate attention. This is partly due to the urgency of managing mounting waste volumes in rapidly urbanizing areas and the visible role and impact of recycling in waste management. However, this focus can result in a narrow approach that neglects upstream strategies like waste reduction and reuse, which offer more significant environmental and economic benefits.

Globally and increasingly in India, there is now recognition that the 3R framework needs expansion to reflect the complexity of urban ecosystems and consumer behavior. Newer models now incorporate additional principles such as refuse, rethink, repair, refurbish, and remanufacture. These additions provide clearer pathways and more comprehensive options for reducing resource extraction and extending product life cycles. Such a reframing helps cities and stakeholders better plan interventions across the entire material lifecycle rather than treating waste at the endpoint.

To mainstream these expanded frameworks, cities must integrate circularity into urban design, procurement systems, and service delivery. Urban planners, administrators, and policymakers need to look beyond waste processing infrastructure and consider systems that prevent waste generation in the first place.

A report by the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs estimated that India could unlock close to USD 3 billion annually through the adoption of circular economy strategies in municipal solid waste and wastewater sectors. Of this, approximately USD 1.7 billion is projected from solid waste streams, and USD 1.2 billion from wastewater and sludge. Realizing this opportunity will require Indian cities to focus on three foundational pillars: robust data and intelligence systems, assured feedstock and product offtake, and enabling governance and policy structures.

1. High-Quality Data and Waste Intelligence

It is often said that what cannot be measured cannot be managed. Over the last decade, the Swachh Bharat Mission, Swachh Survekshan, and the Garbage Free Cities (GFC) framework have played transformative roles in strengthening India’s urban waste data ecosystem. Digital portals, citizen feedback systems, city performance dashboards, and infrastructure mapping have made it possible to collect and visualize data in ways that were not possible earlier.

However, the presence of data alone does not translate into effective decision-making. In many cities, data collection is extensive but not necessarily strategic. Municipal bodies often gather more data than needed, while not using critical datasets for planning and investment decisions. Moreover, some of the most essential data—such as updated waste composition, accurate quantification, seasonal variation, informal sector diversion rates, or mass-flow of waste through the city—are either missing or based on outdated studies.

Cities typically rely on per capita waste generation norms and weighbridge data at secondary collection points for waste quantification. These indicators, while useful, are insufficient for circular economy planning. For example, if the informal sector diverts recyclable material before the waste reaches a weighbridge, the total waste generation will be underreported. Similarly, per capita waste generation metrics cannot accurately reflect changing consumption patterns, especially in a country where product usage is rapidly evolving with growing e-commerce and disposable income.

Updated and localized waste composition studies are rarely conducted, and the absence of this data can result in poor decisions in technology selection, facility sizing, and financial modeling. Without a realistic understanding of waste types and volumes, cities risk creating infrastructure that is either underutilized or overburdened.

There are several examples of Indian cities establishing processing plants that, even after years of continuous operation, never reached their defined optimal processing capacity and ultimately became non-functional. All metro cities in India have faced such challenges, primarily because operational planning did not account for accurate datasets and on-ground reality. Even when the required quantum of waste feedstock is available, its composition, quality, and consistency of supply remain critical planning components. This highlights how the failure to create and leverage accurate datasets can become a key factor leading to the eventual failure of such infrastructure.

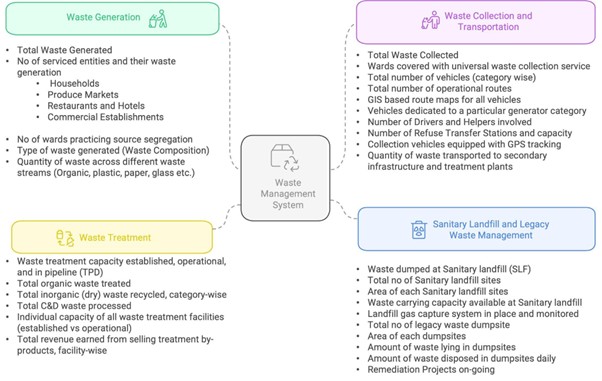

While there are multiple frameworks and reporting structures that enable cities to collect and manage various datasets, the figure below showcases the most foundational datasets a city must have for effective management and efficient circular economy planning.

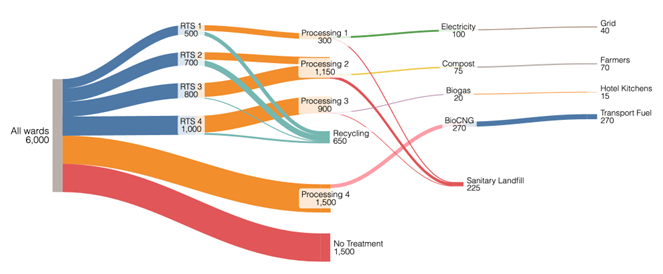

A critical yet often underutilized approach in urban waste management is mass flow mapping. By tracking how waste moves from various city zones through collection, transfer stations, and processing or disposal sites, cities can gain actionable insights into system performance and efficiency. This approach helps identify operational gaps, highlight under- or over-utilized facilities, and optimize logistics and costs. More importantly, it offers a systems-level view of material flows, essential for strategic planning and infrastructure upgrades. A representative example of such a mass flow for a sample city is shown below, capturing material pathways, output products, market linkages, and treatment shortfalls that require planning attention.

When visualized through tools like Sankey diagrams, mass flow mapping clearly illustrates how waste is converted into outputs such as compost, RDF, recyclables, and biogas, along with associated revenue streams and capacity gaps. These diagrams reveal not only current performance but also areas where intervention is needed, making them invaluable for data-driven decision-making.

In conclusion, use of high-quality, granular, and dynamic data must become the bedrock of circular economy interventions. This data should not remain limited to internal or external dashboards but should actively guide decision-making on every step of the waste value chain—from generation to final processing and market integration.

The Swachh Bharat Mission has succeeded in laying a robust foundation for data-driven governance. Cities must focus on institutionalizing data use, ensuring inter-departmental access to information, and embedding data-informed planning into all urban management functions.

2. Securing Input and Output Viability:

The Inflow-Outflow Imperative

One of the most critical yet overlooked aspects of a functional circular economy model is the assurance of consistent and high-quality material inputs to processing facilities, and the corresponding market offtake for their outputs. The construction of waste processing plants alone does not guarantee a successful intervention. For facilities to operate at optimal efficiency throughout their lifecycle, both ends of the system—input feedstock and output product—must be secured and integrated into the broader economy.

On the input side, the most common challenge is the lack of properly segregated waste reaching the facilities. While the national narrative has long emphasized the importance of source segregation, implementation remains a major gap. The absence of segregation affects the purity of waste streams, making processing more expensive, reducing product yield, and in some cases, making the entire facility financially unviable.

For example, a composting or bio-CNG plant requires organic waste with minimal contamination. If the input waste is heavily mixed with plastic, glass, or other non-biodegradables, not only do the quality and quantity of output products suffer, but the overall system efficiency is also compromised, leading to additional costs that are often not accurately accounted for. Technologies can compensate only to a limited extent. Plant design specifications do not change based on ground-level challenges, and therefore, the responsibility falls on the city to ensure a consistent supply of acceptable feedstock. The model in which the municipal body is responsible for waste segregation and collection, while the private sector handles processing, has proven to be more effective than the approach where the city provides only the land and delegates collection, transportation, and processing entirely to a private entity. This clear distribution of responsibilities helps de-risk investments and enhances accountability.

On the output side, the conversation shifts to markets and value realization. The success of a circular economy model depends not just on processing waste, but on integrating the by-products into viable markets. Compost must find end users among farmers or landscaping services. Bio-CNG must be linked to users as transport fuel or industries for their energy needs. A major bottleneck is often the absence of predictable offtake, which discourages investment and scale. Cities should lead by example through public procurement mandates that prioritize circular materials. At the same time, market development requires transparent certification systems, quality labeling, and often cost parity through subsidies or tax benefits.

The role of the public sector as a first adopter is also critical, as it not only creates demand but also sends strong market signals to private players. Indian cities have already demonstrated good practices — bio-CNG from municipal plants powering public buses, compost being sold to farmers through cooperative networks, and plastics recycled into road construction materials. The key is to make these models consistent, integrated, and replicable across geographies. Ultimately, unless both the input and output ends are planned with precision and accountability, the facility risks becoming underutilized or unviable. The circular economy must shift from being merely infrastructure-centric to becoming value-centric, with material flow and market alignment as its guiding principles.

3. Policy, Governance, and Institutional Enablement

A supportive policy environment, backed by institutional clarity and administrative readiness, is fundamental for any circular economy model to move from pilot to scale. In India, national-level schemes such as GOBARdhan, SATAT, the National Bioenergy Programme, and various state-specific circular economy roadmaps have built strong momentum. These initiatives provide clear policy signals, financial incentives, and technical support to promote resource recovery and green enterprise.

However, city-level implementation often lags due to institutional fragmentation and limited technical capacity. Urban local bodies need a designated unit or team responsible for circular economy planning and integration. Given the daily pressure to keep the city clean and ensure 100% collection coverage, waste management is often viewed as an operational task rather than a strategic function that connects environmental, economic, and climate agendas.

To address this, cities need to create dedicated circular economy cells or units that are empowered to coordinate across departments such as sanitation, planning, environment, transport, and procurement. These units should be supported with capacity building, performance-linked incentives, and peer learning opportunities.

In addition, states can play a facilitative role by:

- Issuing clear operational guidelines on circular procurement

- Establishing state-level circular economy innovation platforms

- Creating challenge grants or blended finance instruments

- Standardizing contract structures for public-private partnerships in waste recovery sector.

Finally, institutional enablement should focus on integrating circularity into broader urban policy instruments. Master plans, mobility strategies, climate action plans, and infrastructure investment programs must include the circular economy as a cross-cutting priority.

Conclusion: From Vision to Action

India today stands at a strategic inflection point. With its cultural ethos of minimal waste, a robust policy framework, improving data systems, and demonstrated pilot models, the conditions are ripe for making the circular economy a central pillar of its urban future.

However, for this to happen, intent must be translated into action. The circular economy must be seen not just as a waste management paradigm but as a multidimensional development strategy that creates green jobs, strengthens local economies, improves public health, and builds climate resilience.

The path forward lies in operationalizing systems thinking, institutionalizing high-quality data use, aligning feedstock and offtake mechanisms, and creating governance structures that allow flexibility, innovation, and accountability. Only then can circularity move from being a promising idea to an everyday practice in India’s urban transformation.